Dave Malloy's Moby-Dick Musical Is a Whale of a Time

Director Rachel Chavkin premieres an immersive adaptation of Herman Melville’s novel.

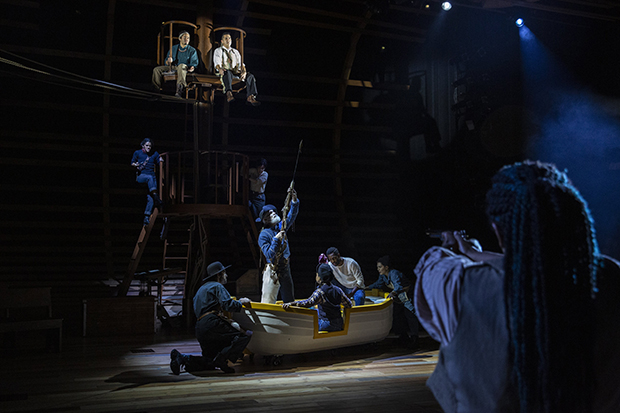

(© Maria Baranova)

Dave Malloy turned War and Peace into a Tony-nominated electropop opera, dramatized Internet addiction through eight-part a cappella harmonies, and turned Rasputin into an indie rock star. If there's anyone who could bring Herman Melville's Moby-Dick to the stage, it's him.

Call me Exhausted. Malloy's Moby-Dick, currently having its premiere run at Cambridge's Broadway incubator, the American Repertory Theater, runs a whopping three hours and 25 minutes — 205 riveting, infuriating, audacious minutes that simultaneously adapt the Melville novel as a musical, recast the author's intentions in contemporary America, and create a new version of the art form: the musical as an amusement park ride. The show itself is wildly ambitious, and so is the production, which could only be the brainchild of director Rachel Chavkin.

The surface of Moby-Dick is the plot of the book: Sailor Ishmael (Manik Choksi) documents his journey on the whaling ship Pequod, where its captain, Ahab (Tom Nelis), is obsessively determined to get revenge on the giant white sperm whale that ate his leg.

However, there's a reason why the show is subtitled A Musical Reckoning. Malloy is coming to terms with America's past and present, and with a novel where everyone is male and most are of one skin tone. Choksi serves as both Ishmael and our narrator, a young man disenchanted with the state of America but who sees Melville's text as a realization of the "sprawling mess" that is our country. We disappear into the version of the Pequod he wants to imagine, where its denizens are all portrayed by artists of color and different genders. The only character played by a white actor is Ahab, and Malloy's Moby-Dick becomes an allegory about the destructiveness of unchecked white privilege, where one man's hubris leads a literal boatload of people to their doom.

(© Maria Baranova)

Divided into four parts (plus prologue and epilogue), Moby-Dick is tonally all over the place, mirroring the literary eclecticism of the source material. There's a half-hour jazz opera devoted to the travails of tambourine-playing ship hand Pip (Morgan Siobhan Green); a patter song about cannibalism by Polynesian harpooner Queequeg (Andrew Cristi); a hilarious religion-bashing, theater-criticizing monologue by the Parsee harpooner Fedallah (Eric Berryman, hilarious); and a vaudeville show complete with life-size puppets (designed by Eric F. Avery) to cover the sections of the novel Melville spends discussing cetology (the study of whales). It's all unapologetically Malloy, encompassing intelligent lyrics, soaring melodies, and polyrhythmic sounds used to mirror the communication style of whales. There's no theater composer writing today whose work is as thrilling to me as his.

The same can be said of Chavkin as director. She brilliantly uses her designers to help mirror the style of each section. Bradley King's lighting is playful early on, becoming darker and more forceful as the chase for the white whale reaches its climax. It also draws attention to different aspects of Mimi Lien's set, which simultaneously blends the ideas of ship, church, and whale belly as it extends over the audience. Brenda Abbandandolo's costumes give a nod to the contemporary, as do Avery's puppets, which, pointedly, are made out of the kind of plastic bottles and other garbage you might find polluting our oceans. (Chavkin really struts her stuff in the second half of the first act, where audience members are invited to join the cast and traverse the stage in four life-size boats, à la "It's a Small World" at Disneyland. It just needs to be seen to be believed.)

Moby-Dick is an ensemble piece, but Malloy and Chavkin allow each of the 13 cast members to have a moment in the spotlight. Choksi instantly wins us over as Ishmael, while Nelis, who could afford to enunciate a little better, is a perfectly myopic antagonist. Berryman is a scene stealer and Starr Busby is particularly haunting as first mate Starbuck, ending the first act with a top-notch Malloy song called "Dusk." I wish Malloy was more explicit in his retelling of Ishmael and Queequeg's intimate relationship, since it's the closest thing the show has to a romance, and I similarly wish they leaned into their gender nonbinary reading of Queequeg with more clarity (the character wears a chest binder throughout). Cristi is excellent and just deserves more to do.

Will there be cuts as Moby Dick continues its journey? Undoubtedly. Nothing needs complete removal, but the fat could be trimmed here and there without losing what makes the show special. Still, I wouldn't have traded the experience for the world, especially since, given its size, this version will likely never be repeated again (just like Natasha, Pierre & The Great Comet of 1812 at its tent in the Meatpacking District). Malloy and Chavkin are well on their way to capturing their most impressive collaboration yet, and I'll be first in line at its next port of call.

(© Maria Baranova)