Choose Your Own Adventure With Jonathan Pryce and Eileen Atkins in The Height of the Storm

(© Joan Marcus)

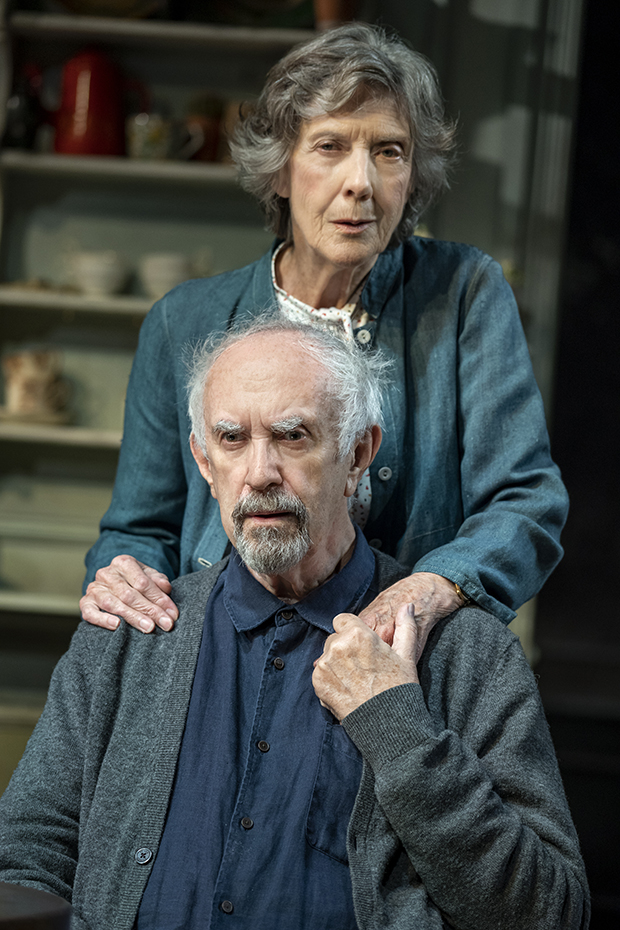

The Height of the Storm is practically the definition of theater as an event. It offers a rare opportunity to see two high-caliber stage actors — Olivier winners Jonathan Pryce and Eileen Atkins — back on Broadway after 13 years. Manhattan Theatre Club's production at the Samuel J. Friedman Theatre, a transfer from London's West End, is a worthwhile ticket for that fact alone. But Florian Zeller's play, translated by Christopher Hampton and directed by Jonathan Kent, is also an enormously moving experience, particularly for those who've loved a partner so deeply that it's hard to imagine ever being without them.

"You think people are dead, but that's not always the case," says André (Pryce), a famous writer who seems to be in the throes of dementia. His hand shakes with a tremor, and he is barely able to squeeze into his usual chair. As he speaks with his daughter, Anne (Amanda Drew), we learn that André has recently lost his wife of five decades, Madeleine. Then Madeleine (Atkins) arrives home from the market and behaves as though she is the bereaved, making good on a longtime promise to outlive her husband. Or has she?

A riddle wrapped in an enigma sautéed in a mystery, The Height of the Storm is like a choose-your-own-adventure novel. I counted at least five different stories being told within the ellipses and fragmented shards of conversation in Zeller's 80-minute text. He doesn't provide us with easy answers — he doesn't provide us with any answers, really — and that allows us to interpret the meaning of the material as we see fit. But when Zeller gets to the heart of this matter of love, loss, and grief, which is unpeeled as methodically as Madeleine taking the skin off mushrooms, the final scene becomes an emotional doozy that will haunt you for days.

Pryce and Atkins provide two stunning turns that are a study in contrasts. Pryce is authoritarian, imperious, and downright frightening at times, while still being so vulnerable and frail that a small breeze could knock him over. His multifaceted, full-bodied performance is so convincing that you may even wonder if that tremor in his hand is real.

Atkins, meanwhile, is straightforward, world-weary, and mordantly funny, with a gaze that shoots daggers. It's like watching two people who have been married for decades; their undertones are filled with love, devotion, frustration, and sadness.

Kent has assembled a terrific company of actors and designers alike. The vastly different personalities of André and Madeleine's children are entirely distinct in the hands of Drew and Lisa O'Hare, while Lucy Cohu and James Hillier mysteriously complete the company as two potentially nefarious characters simply called "The Woman" and "The Man." Anthony Ward designs a spacious Parisian country home with robin's-egg-blue walls, graying mirrors, and high ceilings. The real coup, though, is Hugh Vanstone's lighting, which not only changes the tone of a scene, but somehow manages to shift the entire plot through a simple raising or dimming into blackness.

Though The Height of the Storm has a tendency to meander, it really is difficult not to be taken under its spell. It's worth the price of admission for Pryce and Atkins alone, and their unforgettable performances won't disappoint. Bring a pack of tissues, too.

(© Joan Marcus)