In Hadestown, What Is Myth and What Is Musical?

Find out how (and why) Anaïs Mitchell took creative liberties with her mythological characters.

Hadestown, Broadway's 14-time Tony-nominated musical by singer-songwriter Anaïs Mitchell, borrows the myths of Orpheus and Eurydice, and of Hades and Persephone and marries them in a New Orleans jazz-folk-musical retelling of the ancient Greek tales. With Tony-nominated director Rachel Chavkin at the helm, the musical mostly stays true to the traditional stories, but it sneaks in some creative liberties to enrich its own romantic mythology.

If you're curious which elements of Hadestown's main characters are original and which are artistic embellishments, we've parsed it out so you don't have to.

Orpheus

(© Christian Gottlieb Kratzenstein-Stub / Wikimedia Commons / Matthew Murphy)

Orpheus's mythological reputation is as the greatest of all poets and musicians who could enchant even nonliving things with a song on his lyre. That remains the case in Hadestown. His power of song is still his ticket to the underworld, but in Anaïs Mitchell's rendering, it's also the remedy for weather gone awry. The shifting currents of love between Hades and Persephone (who is responsible for bringing her "suitcase full of summertime" above ground every six months) are throwing off the rhythms of the earth, and Orpheus's melody is the only thing that can return the seasons to their natural balance. Of course, Orpheus's main objective in visiting the underworld is to retrieve his love, Eurydice, but Mitchell uses her protagonist's musical prowess to conflate two love stories in order to illustrate how art has the power to set the world back on course.

Side note: In the traditional story, Orpheus responds to his heartbreak over Eurydice by turning exclusively to homosexual relationships before being torn to pieces by maenads. But maybe Mitchell will get around to those details in a sequel.

Eurydice

(© Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot / Wikimedia Commons / Matthew Murphy)

The most significant alteration to the story of Eurydice is a giant dose of life-affirming (and life-condemning) agency. Hadestown takes a mythological character whose life is stolen by a poisonous snake bite and turns her into a woman who voluntarily makes the trip "Way Down Hadestown." Death is a choice for this Eurydice — as is leaving behind her beloved Orpheus, who distractedly toils away at his songwriting while she grows cold, hungry, and desperate for stability. Traveling to Hades's corrupt underworld may not have been the right call, but Eurydice makes an active choice to explore her curiosities and satisfy her own needs. It's perhaps the most pivotal difference between the myth and the musical — and what a powerful way to eliminate the wilting flowers from a theater overrun by red carnations.

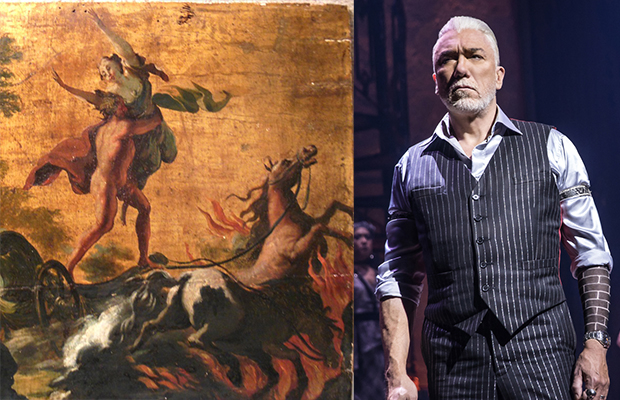

Hades

(© Wikimedia Commons / Matthew Murphy)

Contrary to the musical's story, the mythological Hades does not specifically seek out Eurydice as a replacement for his ungrateful wife. In Hadestown, Eurydice is enticed by the life of comfort and protection provided by the underworld, just as Persephone becomes increasingly disillusioned by it (and her tyrannical husband, who rules over it like the CEO of ExxonMobil). Hades sings to Persephone, "If you don't even want my love, I'll give it to someone who does; someone grateful for her fate; someone who appreciates the comfort of a gilded cage." That someone is Eurydice, creating a twisted love triangle (or square, if you include Orpheus) that adds a new layer of stakes to the familiar pair of myths. The traditional Greek Hades also does not run an underground foundry that produces "coal cars and oil drums," but that modification is probably easier to spot.

Persephone

(© Frederic Leighton / Matthew Murphy)

A brief summary of the story of Persephone: Hades falls in love with her, gets permission from her father, Zeus, to abduct her, and brings her to the underworld to become his wife. Persephone's grief-stricken mother Demeter, goddess of harvest and growth, triggers global famine, which leads Zeus to agree to retrieve their daughter if it can be proven that Persephone is with Hades against her will. Hades then tricks Persephone into eating six pomegranate seeds, tethering her to the underworld and prompting the compromise that she would spend six months every year underground and the remaining six months on Mount Olympus with her mother (hence the seasons we have now). Hadestown is faithful to the story, including the unlikely love bond that develops between Persephone and her captor husband. Perhaps the only embellishment is Persephone's propensity for "Livin' It Up on Top" during the spring and summer months. She's theoretically returning to the world of the living to be with her anguished mother, so you'd assume their bonding time would be less debauched. But it is the ancient Greeks — so you never know.

Hermes

(© Giovanni Battista Tiepolo / Matthew Murphy)

Mitchell cleverly turns the messenger of the gods into Hadestown's omniscient narrator. As the "conductor of souls," we watch him introduce his railroad line to hell and usher Eurydice into the underworld. But the musical adds a few more layers to his persona, molding him into a paternal presence for Orpheus as well. In mythology, Hermes is known as a trickster, but in the world of Mitchell's musical, he's more a facilitator and a champion — notifying Orpheus of Eurydice's underground exodus and encouraging his long journey to recover her. Of course, through all of this, Hermes knows that the story of Orpheus and Eurydice has a tragic ending. But you can't accuse him of ambiguity when the man tells us up front:

It's a sad song.

It's a sad tale, it's a tragedy.

It's a sad song.

But we sing it anyway.