Interview: Patrick Page on Shakespeare's Villians and Building All the Devils Are Here

The ”Hadestown” Tony nominee discusses his new streaming solo show for Shakespeare Theatre Company.

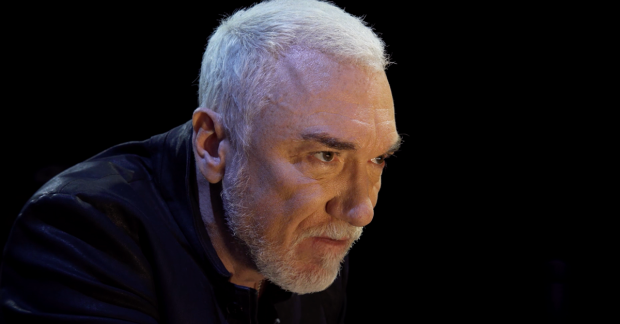

Today, Shakespeare Theatre Company begins streaming Patrick Page's All the Devils Are Here, a new solo show about the evolution of evil in Shakespeare's villains, from Macbeth to Claudius. Page, a Tony nominee for Hadestown with a wide variety of Shakespeare's heroes and villains under his belt, recently told us about the production and its evolution. You can stream the show here.

image provided by Shakespeare Theatre Company)

This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Is this a new piece, or one that you've been developing for a while?

This is really its coming-out party. I have done the show in a series of previews up to now, and I would call even this a preview in a way, because I do hope eventually to bring the show to New York, and I'll continue working on it.

But I had a notion of doing an evening of villains for a long time, almost a decade. I knew which characters I wanted to do, but I didn't have any organizing idea around them. And then one day, it occurred to me to move chronologically though Shakespeare's canon, starting at the very beginning of his career, and see how his feelings toward these people changes and deepens. I tried to trace the events in his life and history that might have shaped those changes. It became a detective story for me.

The subplot of that was, Shakespeare is handed this tradition of the revenge tragedy, which he kind of had to write, and did so in Titus Andronicus, very early in his career. But I think he always felt uneasy about the human instinct for revenge. He wrestled with that in Hamlet, and came to some kind of resolution about it in The Tempest.

Those two through-lines guided me, and are still guiding me as I revise and improve the show.

How did the filming come about?

I had written Simon Godwin, the new artistic director of Shakespeare Theatre Company, to see if there was any interest, and he invited me. We set up to film in the Harman Theatre under Covid conditions: masked, distanced from everyone, no touching anybody. By everyone, it's a very small crew: one cameraman with a moving camera, two stationary cameras on the sides of the stage, and the director, Alan Paul, at the back of the house.

The moving cameraman, he is really a co-creator of this, because he just did this dance with me. There was no one to tell him where to move — Alan didn't have a monitor and he wasn't on a headset — so he just made decisions. He would come around me and I would work off him the way I'd work off another actor. We shot it wice, but not with any sense of having to meet the same marks, so a lot of the shots don't match, and Alan had to try as much as possible to match them in the editing room. It was a by your bootstraps process, and because of that, I was very surprised and pleased by the quality of the film.

I feel like this is a really good show for students or your sort of younger Hadestown fanbase that might not be aware of the other facets of your work.

I think it could be. I wanted it to be a show that a Shakespeare enthusiast would really love, but even more importantly, I wanted someone who had no knowledge of Shakespeare, or someone who might even be put off by him, to watch and say, "Oh, I see why people say he's such a great writer."

You're also doing a radio play version of Julius Caesar for the company Shakespeare@. You've done the play several times. How did this come about, and how did your past experiences inform your work here?

This wonderful company just asked me, and I said sure. I played Decimus Brutus in New York with Denzel Washington, and I had played Mark Anthony at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, and Brutus at the Utah Shakespeare Festival. Now I've played Caesar, but I really would still like to play him onstage, and he can be much older, so I feel like I have years to do that.

In each production, I've always had an opinion of who I thought Caesar was. Caesar is a very economically written role. It's a very small part, and he disappears. There are two whole acts essentially without him in it, except for when his ghost pops up. In the economy of that writing, there's an opportunity to show all aspects of this titanic historical figure: his narcissism, his greatness, his physical infirmity, his fallibility, his love for his friends, his loyalty. I've seen actors get this aspect, or that aspect, and I really wanted to see if you can flesh all of him out. The actors who've done it in the other productions I've been it have been wonderful, but you always have your own ideas.

How much do you miss doing Hadestown?

I miss Hadestown enough that the other day, I put on headphones and listened to the whole thing through. Which you wouldn't think a person would do if you have to hear it eight times a week, but it was amazing coming back to it. I really experienced once again how good it is, how beautifully it's constructed, how insightful the lyrics are, and how contagious and evocative the music is.

I asked Anaïs Mitchell a version of this question last summer, but how excited are you to perform "Why We Build the Wall" without the global connotation of that song?

I will be so happy when I sing those six words – "why do we build the wall" – and three quarters of the audience doesn't immediately have an orange man popping into their mind. I did it before Donald Trump was politically a force — at New York Theatre Workshop, he was just starting to emerge and it wasn't yet central. By the time we got to Canada with it, it was central, but they were Canadian, so they weren't making the same kind of direct link. When we went to London, they had a broad enough sense of the world that it wasn't the only thing they thought of. But when we got to Broadway, it was pretty much all people thought about when I began that song. The song, of course, is about so much more than that. The metaphor of the wall – all the walls we build around each other for all kinds of reasons — is so powerful. I will be grateful when the largeness of that metaphor returns to the song.