Interview: Drew Larimore and Michael Urie Explore a Small-Town Tragedy in Smithtown

Urie and Larimore discuss social media and technology in an eerily prescient play.

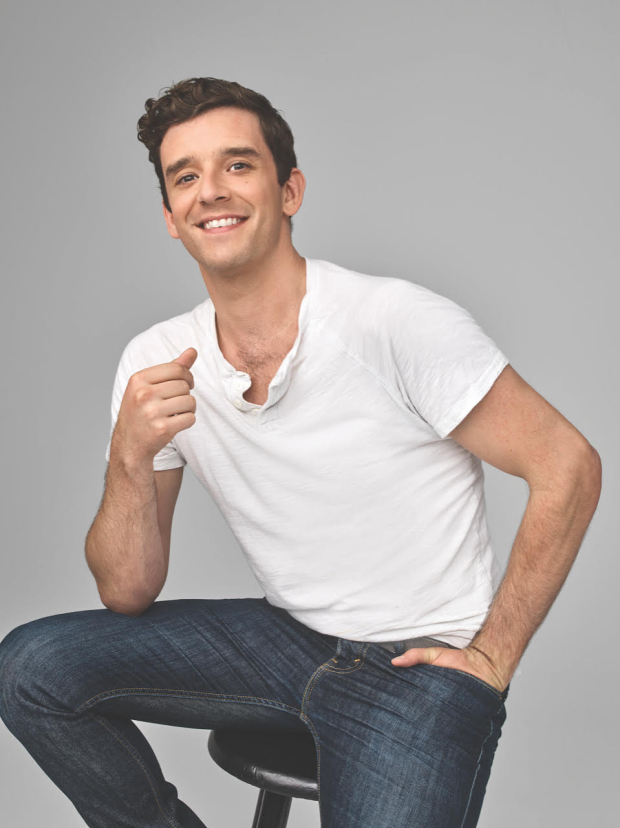

(image provided by the production)

Drew Larimore's career can be described with a variety of titles, including playwright, librettist, and screenwriter. But the upcoming virtual production of Larimore's play Smithtown could result in another descriptive being added to his LinkedIn profile: clairvoyant.

A four-part series of monologues linked together by a local tragedy, Smithtown, streaming February 13-27, offers a penetrating look at the impact of technology in everyday relationships. Chronicling the harrowing ripple effects of a careless word or action, the play is a haunting and undeniably timely portrait of disconnect in an age of digital connection.

It's also 10 years old. Larimore, who first wrote the script while on a cross-country flight to Los Angeles, never thought Smithtown would be produced. But a decade passed, Covid struck and he dusted off the script. Not only was the play still relevant, the four-monologue structure was perfectly suited for the virtual theater format being employed throughout the pandemic.

"Everyone thinks I wrote it yesterday but it's actually a much older piece," Larimore said. "I wrote it initially because I'm just interested in general – ethically, morally, societally – about technology and who bears the brunt of misbehaviors through technology, particularly when it involves a cascade of people."

That cascade of people in Smithtown is represented by Michael Urie, Ann Harada, Colby Lewis, and Constance Shulman, each playing a different member of the small-town community and each involved, separately in a local tragedy.

(© Konrad Brattke)

Despite the years that have passed, Larimore said only 10 percent of the script – which examines the privacy of written communication, the instinct to record events rather than participate in them, and the authenticity of connections that never include human interaction – had to be updated.

Streaming shortly after the end of Donald Trump's presidency and a political insurrection planned through social media, the play feels eerily prescient. The ease of sharing personal photographs via cell phones is chronicled in the opening monologue, performed by Urie as Ian Bernstein, a graduate student whose embittered actions immediately following a breakup set off the heartbreaking events in the city of the title.

Leading a class on ethics and technology, Urie's scene explores, at times reluctantly, personal responsibility and accountability within digital communication. Cause and effect, and intention and action are called into question, but he is unable to find any answers.

Urie savored the challenge of playing Ian, a character unlike many of the comedic, high-energy roles he has performed, including Jonathan Tolins's one-man tour de force Buyer and Cellar, Nikolai Gogol's ensemble satire The Government Inspector, and Harvey Fierstein's Torch Song. Ian, Urie said, is a sociopath, and understanding his motivations was crucial to the performance.

"It's such a clever device that Drew came up with," Urie said. "[Ian] just happens to be teaching a class in the thing that he did. Whether the class created the man or the man created the class, you never know. He's so uniquely qualified not only to teach the class but to recount this experience anecdotally. It is such a uniquely cis white man confidence that he thinks he can just get away with it and it can be anecdotal – here he is smiling to his class. I can only imagine what happens next to him."

It was the characters' flaws that hooked Larimore throughout his writing he said. When watching the recording of Smithtown, the playwright experienced a visceral reaction to Ian, despite having created the character himself.

"It was like I hadn't written it, like I was watching it for the first time," he recalled. "He's a pretty despicable guy and he starts off this play in a crazy way. It's a back and forth – liking this character, relating to his mistakes and also expressing disapproval. The first time I saw it, about three fourths of the way though, I said under my breath, 'What a dick!' … I think I fell in love with where they went wrong. I do relate to using texting or sending the wrong text or saying the wrong thing. I really relate to their screwups and how that haunted them."

(image provided by the production)

That relatability is timeless, Urie said. "Drew wrote this 10 years ago before Trump ascended to the presidency on social media – and revenge porn is not a new idea – but he sort of predicted the ways in which social media was going to take us down and destroy us. And these kinds of acts, these kinds of crimes, should be held accountable."

While Smithtown's relevance is undeniable, the process of putting the show together was, for Urie, refreshingly old-fashioned. A constant presence on computer screens throughout the pandemic – Urie reprised his role in the one-man show Buyer and Cellar from his dining room, discussed Shakespeare in Red Bull Theater's Monday night conversations, and was the host and only audience member of Audra McDonald's gala at City Center – the actor has missed the process of putting a show together and watching it unfold.

"I miss doing [theater], but I also miss watching so much," Urie said. "Watching the actor put it together. Watching the piece unfold as it was intended to unfold after weeks of preparing. That's one of the things about theater that's so thrilling that we are missing now so often. That was part of why we went was to see the creation."

When preparing for Smithtown, each cast member rehearsed with director Stephen Kitsakos before filming their monologue. Despite being well-rehearsed, Urie had pre-performance jitters – just like before he would go in front of a live audience.

"The longer we've gotten into this pandemic the more I've quietly realized what it is about the theater I really miss," he said. "At first it was: I miss the people, I miss having an audience, and then it was, I miss that kind of work. A play really should send you out of the theater thinking about what you just saw, talking about what you just saw. And with the theater, even with something fluffy, it's meant to stay with you. And certainly Smithtown is that – something that says with you and spurs discussion and introspection."

Get tickets for Smithtown, presented by the Studios of Key West, here.