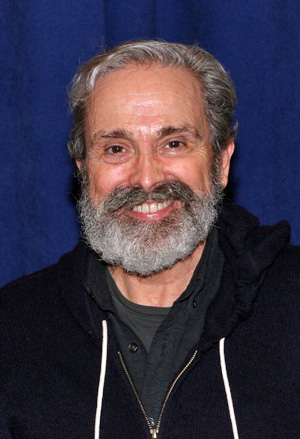

Craig Lucas on An American in Paris, New York Audiences, and Why Book Writers Get No Respect

The Tony-nominated playwright is part of the team bringing a new adaptation of the classic MGM film to the stage.

(© Angela Sterling)

"I can guarantee that for any new musical I work on they're going to say, 'The only bad part is the book,'" predicted playwright Craig Lucas, nonchalantly adding, "I got used to that years ago. I can live with that." Lucas is an author of plays (Reckless), librettist of operas (Two Boys), and book writer of musicals (The Light in the Piazza). He considers the latter the most difficult of his many jobs, which might explain his Zen attitude when it comes to reviews. "What I want is a musical that works on all levels," he said. He feels like he has that with his latest project, An American in Paris, which is now previewing at Broadway's Palace Theatre.

Based on the beloved 1951 film starring Gene Kelly and Leslie Caron, the show follows American GI Jerry Mulligan as he makes his home in Paris after the allied victory over the Nazis. He falls in loves with the beautiful and enigmatic Lise Dassin, but she is already engaged to manufacturing heir Henri Baurel. Like the film, the show features the music of George Gershwin, including an extended ballet sequence set to his symphonic poem "An American in Paris." "I was very interested in the ballet," Lucas said. "I wanted it to have a role in advancing the plot and the characters."

Lucas spoke with TheaterMania about the changes he's made to Alan Jay Lerner's original screenplay, the differences between Paris and New York audiences, and the reason why book writers get such a bum rap.

(© David Gordon)

You've adapted a well-known film for the stage. Did you feel a certain tyranny of expectations?

I didn't. People have great affection for the movie, but if you ask them about it (Who are the characters? What do they do? Why?), they don't remember. That is not the most memorable thing about the film. The most memorable thing is the music and Gene Kelly. I didn't think you could do it without the characters. You'd have to call it something else. I was only interested in doing this if it would be an opportunity to do something theatrically innovative or to play with the narrative in a way that brought something new.

You've definitely played with the narrative, moving the time period from the early '50s to 1945. Why?

There's a lot more to be said for the period immediately following liberation in terms of the intensity of people's feelings. It wasn't a foregone conclusion that Paris was ever going to be the same. If you want to tell a story about people finding love and hope in the face of devastation, start in the shadows. Also, the film raises certain questions: Why didn't Henri fight? Why was Lise in hiding? Why isn't Jerry going home? Who were these GIs who stayed in Europe? It's almost an invitation to look at these circumstances with the knowledge the last sixty-five years have given us.

(© Angela Sterling)

Do you feel that 1951 audiences weren't prepared to talk about certain aspects of the war?

I know they were not eager to return in their thoughts to painful subjects that were so recent. My father fought in World War II. He and his friends all said, "Oh, those were the greatest years of my life." But if you asked them what fighting was really like they would say, "You don't want to know that." These were men who were expected to put it all behind them and not be weaklings with fears or doubts or any trepidation. But you don't kill people (whether they're Nazis or not) without a cost. I was interested in a man who didn't want to go home because he didn't want to be held up as a hero. He felt that what he did was necessary, but not something to crow about. This audience seems very welcoming of the shadows that might not have been possible in the 1950s.

This show had a lengthy out-of-town tryout in Paris. What was that like?

It was crazy fun. Jean-Luc Choplin, the man who runs the Théâtre du Châtelet, has created an audience for American musicals in Paris. They perform them in English. I was thinking, They're not going to get the jokes, but they got all the jokes and references. They laughed at everything! The show was considerably longer in Paris than it will be in New York, but no one got bored or walked out. You do a show in New York and even people who love it race out of the theater to get a taxi.

Is there a big difference between Paris and New York audiences?

They're both sophisticated about their culture. Audiences on Broadway are more accustomed to having things clarified for them. I wouldn't say they're hungry for difficulty. There was a time in intelligent circles where difficulty was considered part and parcel of one's engagement with important art. You didn't sit down to read Ulysses and expect it to explain to you why it took the form it did. You had to do that work. We're now in a period where there is a generally accepted ethos where if you have to stop and talk with your friends or look up a word in the dictionary, the work is flawed. That is a larger battle that I can't assume for myself because this is a commercial musical. I do have to take care of the audience and explain things to them. You don't want the really bright kids to fall asleep, however, so you put in references they'll know.

Is that the role of the book writer?

The book writer is really the caretaker of the story. What's sung in a song or what kind of song is often determined by the book writer. You read these reviews where they say, "There's really no book." Well, any musical that has a story has a book. The book writer is always there to watch over the story. It's not just about writing funny lines.

So why do you think people so often blame the book when a musical doesn't work?

They've learned they can say that because they don't know how to write music, they don't know how to choreograph, they don't know how to paint, but they do know how to speak English. So they assume they know good writing from bad. Maybe they do. A really good book is Hugh Wheeler's book to A Little Night Music. A great book is Hugh Wheeler's book to Sweeney Todd. But needless to say, none of the reviews mention Hugh f*cking Wheeler. Of course, if you do shows or plays or art for the reviews, you're doing it for the wrong reasons. If you need people to praise you, become a politician.