Chosen Child

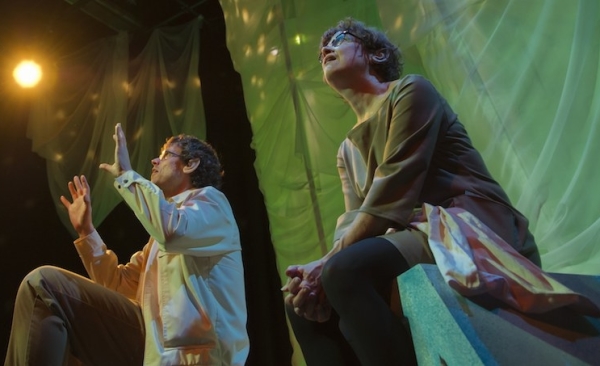

(© Kalman Zabarsky)

Claudia is dead, that much is clear, in Monica Bauer's kernel of a play, Chosen Child, now running at Boston Playwrights' Theatre. However, Bauer has overloaded her work about orphaned children and the life-long anguish caused by their abandonment with so many plotlines that the drama buckles under the weight of the confusion. No one is guiltless in this sad story, based in part on the playwright's true experiences.

Bauer introduces us to a family of women, headed by Grandma Lee (her husband, Pops, never appears onstage), her two adopted daughters, Claudia and Donna, and the one boy, Claudia's son, David. Later on we also meet Anne, Donna's daughter. To say that the generations of women in this one family have made poor choices in their manner of parenting is to understate the emotional havoc resulting from the lies and cover-ups that explode like landmines during the course of the play. The exposition is partly contained in letters, undelivered but then discovered as if Bauer had no choice but to employ an old-fashioned theatrical convention from 19th-century "well-made" plays, in an attempt to untangle the cat's cradle of relationships.

Chosen Child is told in flashbacks, to ricochet from present to past. We meet the grown-up Donna at first, a professor with a Ph.D. in psychology who is estranged from Claudia, her real mother, and has only tenuous ties to Lee, the woman who raised her. Later on, we see Donna as a rebellious teenager, segueing to a graduate student in her mid-20s. Claudia, a deviant personality from a complicated gene pool, is also presented throughout her age span, as is David, the play's only man onstage — and the victim. By the time he is grown, he is a brilliant schizophrenic, but unable to function in society without a mother's protection.

Debra Wise as Donna and Lee Mikeska Gardner as Claudia are not only actors but also artistic directors (of the Underground Railway Theater and the Nora Theatre Company, respectively) who alternate in sharing the stage space at Central Square Theater. Their roles in Chosen Child as written require them to change ages and personalities as they mature before our eyes, within the context of the 90-minute, one-act play. A difficult task, but Wise rises to the challenge, fueling her interpretation of Donna with the burden of anger carried from childhood. Likewise, Bauer makes Claudia into a self-centered, bad seed of a child who never quite grows up. Both women are presented in outline, rather than rounded personalities. Lewis Wheeler delivers a moving portrayal of a young boy deprived of the stability to fulfill his potential, retreating to an inner world he tries desperately to control. Margaret Ann Brady as Lee comes across as a pioneer woman, her regrets coming as a surprise at the end. Melissa Jesser makes smooth transitions between three different roles, creating an especially sympathetic character as the ticket taker who tries to help David.

Director Megan Schy Gleeson keeps the action flowing despite the many changes of scene and timeframes in an attempt to clarify the chronology. The abstract setting of white gauzy pillars and boxes that serve as seats and beds as needed, designed by Anthony R. Phelps, provides a useful frame to the narrative. These set pieces alternate with a counter at New York's Port Authority Bus Station, where David is trying to buy a bus ticket to take him to his sister, Donna, a recurring scene that provides the connecting thread between the various characters.

No doubt, the pain of these revelations motivated Bauer to start this play, but perhaps she needs to distance herself more from the memories. To be sure, some dramatists write what they know, but perhaps stage truth needs to differ from real life to make more of an impact.