The Rolling Stone Recounts an Antigay Witch Hunt in Uganda

Chris Urch dramatizes a call-out culture with deadly consequences.

(© Jeremy Daniel)

If your life is in danger, do you run to safety or stay and fight? Would your answer change if fleeing means leaving your family behind? Every year, millions of refugees and asylum-seekers have to consider those agonizing questions, hypotheticals that precariously hang over the stage of the Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater at Lincoln Center Theater, where Chris Urch's The Rolling Stone is making its off-Broadway debut.

Not to be confused with the English rock band or American music magazine, The Rolling Stone takes its name from a short-lived Kampala newspaper that infamously ran the photos of 100 alleged Ugandan homosexuals next to a little yellow banner that read "Hang them." This was in 2010. The editor in chief of that rag was Giles Muhame, who has never faced any serious legal or professional repercussions for his incitement. Indeed, Muhame is still an opportunist masquerading as a journalist (he is currently the president of the Uganda Online Media Publishers Association). His tale of failing up by never apologizing might have made its own illuminating drama in the age of Trump, but he is not the focus of The Rolling Stone, a delicate family drama that never manages to fully harness the dramatic electricity of its inspiration.

(© Jeremy Daniel)

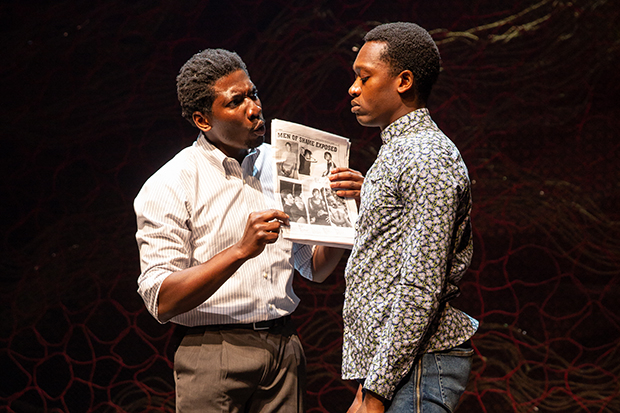

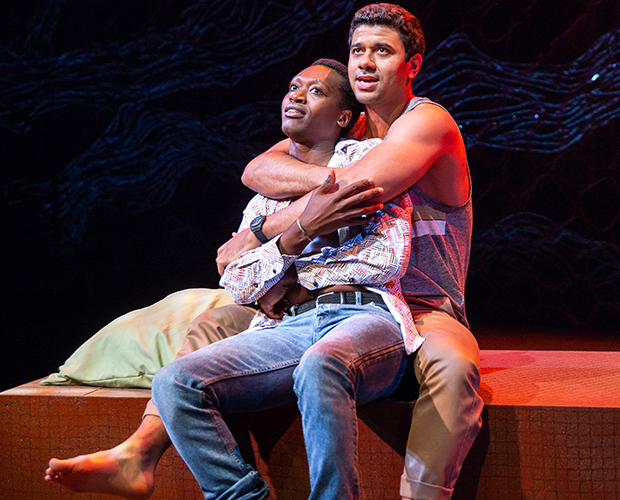

Following the death of their father (a respected Kampala pastor and lawyer) siblings Dembe (Ato Blankson-Wood), Wummie (Latoya Edwards), and Joe (James Udom) gingerly approach their adult lives. While Dembe and Wummie intend to finish medical school with their shares of the inheritance, Joe takes over as pastor of their church and head of the family. He secures this position with a little arm-twisting from Mama (Myra Lucretia Taylor, playing a jolly pillar of the church who is not actually their mother). They all expect that Dembe will marry Mama's suddenly mute daughter, Naome (a heartbreaking Adenike Thomas); but he has fallen in love with a borderless doctor from Derry named Sam (Robert Gilbert). This secret romance threatens to become a public scandal when a newspaper starts publishing the photos and addresses of Uganda's homosexuals, prompting a campaign of terror against them.

Uganda (where one can be sentenced to seven years in prison for "gross indecency," the same charge leveled against Oscar Wilde) is not a great place to be gay, but Urch highlights a period when it was particularly scary. In Joe's sweaty, spitty sermon, Udom captures the collective frenzy that sets in during a sex panic, when fear is just as powerful as fervor in convincing people to join the movement. With exacting realness, Taylor puts a smiling, cheerful face on the blood lust that accompanies any purportedly righteous crusade: "Do you deny it?" she asks Dembe about his alleged homosexuality, sounding very much like John Hathorne in full froth.

(© Jeremy Daniel)

It's hard not to hear echoes of The Crucible in this play and be reminded of how much more acutely Arthur Miller depicts the self-sustaining nuclear reaction of hysteria and vindictiveness that accompanies a sex panic (which both the Salem Witch Trials and the Rolling Stone incident were). Urch has an admirable sensitivity for small human interactions within grander historical moments, but we often feel like we're missing the woods for the trees. Those not already familiar with recent antigay events in Uganda are likely to walk away from The Rolling Stone as mystified as when they walked in.

The dramatic potential of The Rolling Stone is also undermined by Urch's own fashionable politics: A later scene in which Sam offers to take Dembe away to Derry, and Dembe frets about lingering antigay bias in Northern Ireland, feels like perfunctory Western liberal self-flagellation. When you're about to be lynched, you probably don't worry about when you can and can't hold hands in your country of asylum — you just go.

(© Jeremy Daniel)

Director Saheem Ali spotlights the actors in his production, which is a smart move since the performances are the best part, especially a gripping late confrontation among the three siblings. Unfortunately, Ali fails to employ design in a way that would complement the tension they bring to the stage.

Arnulfo Maldonado's set looks like a giant installation one might find at the Whitney Museum: The backdrop is handsome, intricate, and expensive-looking; it is also never activated or referenced by the performers. The vibrant pattern of this backdrop might have been inspired by Dembe's boldly patterned shirts: When viewed next to Joe's ill-fitting and dour suit, they tell the conspicuous story of the gay brother and the straight brother (well-chosen costumes by Dede Ayite). Justin Ellington's music for the church scenes is appropriately lively, but a light piano chord that signals the beginning of some scenes feels a bit too twee for a story this bloody.

And make no mistake: This is a story of violence and cruelty that should shock, even though it is distressingly common. As we in the West descend into internecine conflicts about the corporatization of gay pride and the scourge of "heteronormativity," we ought to remember that in large swathes of the world, just being openly gay is enough to get you killed. Disappointingly, The Rolling Stone never quite conveys the sense of ever-present danger that so many queer people wake up to every morning, and struggle go to sleep with at night.