(© Carol Rosegg)

Chances are that most American theatergoers have never heard of Dr. Noel Browne, the Irish Minister for Health from 1948 to 1951. That doesn't mean that we will walk away from Larry Kirwan's historical drama, Rebel in the Soul, without strong opinions about the man and his mission. Much like progressive crusaders in our own country, Browne fought to expand access to healthcare, regardless of wealth or status. Predictably, he was criticized and hamstrung by those eager to maintain the status quo. Rebel is a tale chock-full of relevance, so why does this world premiere at the Irish Repertory Theatre fail to stir the soul?

Some of it has to do with the way Kirwan introduces us to the story: A series of extended monologues from Browne (Patrick Fitzgerald) and his party leader, Sean MacBride (Sean Gormley), exhaustively establish the exposition before any characters are actually put in dialogue. Some viewers may tune out even before we learn about Browne's impoverished childhood and how tuberculosis claimed the lives of both parents and a beloved older brother. Browne also suffered from the incurable disease, but a series of lucky breaks (a free ride at Catholic prep school and Trinity College) granted him the privilege of access to medical care. This saved his life…for a time.

Throughout the play, Browne is always aware of the ticking clock, an adversarial relationship with time that leads him to push hard for his plan to make healthcare free for all Irish mothers and children up to the age of 16. He doesn't want any children to suffer the same way he has.

(© Carol Rosegg)

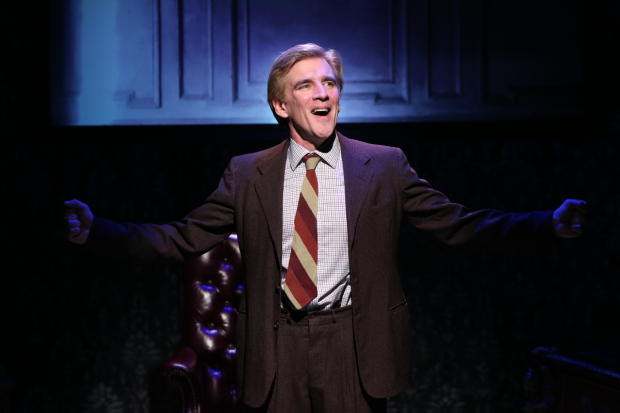

This painful personal history coupled with a feverish drive to see his plan to fruition gives Kirwan's interpretation of Browne the feeling of a superhero — or supervillain — depending on your feelings about socialized medicine. Fitzgerald certainly leans toward the latter in a portrayal that features a crazed gleam in his eye and a grin that arrives at the most inappropriate moments. Sarah Street does a fine job in the underwritten role of his wife, Phyllis. Unfortunately, she seems to be present only to temper our digestion of him, like lemonade in a Guinness Shandy.

Fitzgerald's performance occasionally betrays Kirwan's lazy construction, like when a well-heeled physician (Gormley) shuffles onstage holding a newspaper and muttering about "creeping socialization" and taxation. "How nice to see you again, doctor," Browne says, jumping out from hiding like the Joker in a lesser Batman movie. He promises to force the doctor to open his doors to all patients, no matter how poor. "Of course, my government will reimburse you for each visit — in pounds, however, not guineas," he taunts, barely suppressing a wild cackle. Even if we admire what Browne is doing, it is difficult to warm to such a profoundly affected personality.

Conversely, John Keating is positively charming as Archbishop John Charles McQuaid, Browne's chief antagonist. Ruling over his island like a 20th-century theocrat, McQuaid is wary of anything that smells of godless communism, and that includes Browne's plan. Keating endows the Primate with singsongy diction and a mischievous smile that accents his wit. Still, we understand how pernicious his charm is when we see him in combat with Browne: Separated from the archbishop by a giant wooden desk, Browne resembles a naughty schoolboy more than a government minister. Can Ireland truly be called a republic when an unelected clergyman wields so much power?

(© Carol Rosegg)

Director Charlotte Moore at least makes the context of Irish politics clear in a mostly ham-fisted production. John McDermott's bulky set (two desks and an armchair in a richly wallpapered room) dominates the playing space: McQuaid gets a fully realized office in which to drink tea and pray (which he does in darkness as other scenes go on), but the rest of the stage feels cramped by comparison (perhaps this is a visual metaphor for the wealth and power of the church, but it is one that comes at the expense of Moore's blocking). The costume design by Linda Fisher sometimes confusingly contradicts the script: At one point, Browne mentions the "sober bow tie" he is wearing, and we look down to see a striped necktie under his rumpled suit. Projection designer Chris Kateff and sound designer M. Florian Staab attempt to bring the wider atmosphere of postwar Ireland into the black box theater, but their efforts are too often imprecise: When Browne gives a speech to supporters, they cheer so consistently that it is never clear they are actually listening to any of Browne's words.

Then again, this could just be a comment on the tribal nature of democracy: It doesn't matter so much what my candidate says or does, as long as he's on my side and we are winning. If there is one thing we take away from Rebel in the Soul, it is that sense of continuity in politics.