Riding the Midnight Express With Billy Hayes

In 1970 Billy Hayes was sentenced to life in a Turkish prison for smuggling hashish. He tells his story (including how he got here to tell it) in this new solo show, based on his memoir ”Midnight Express”.

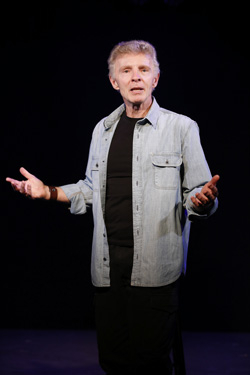

(© Carol Rosegg)

International drug-smuggling just ain't what it used to be. When a 22-year-old Billy Hayes first spirited 2 kilos of Turkish hashish out of Istanbul in 1969, he was able to walk right onto a Pan Am flight with the drugs not-so-cleverly hidden beneath a faux plaster cast. Imagine getting that by the full-body scanners today! By his fourth trip to Turkey in 1970, with airport security tightening after a string of terrorist attacks, Hayes' luck had run out. He was arrested as he boarded the plane and eventually sentenced to life in prison. So how does he find himself telling his incredible story on the stage of St. Luke's Theatre? That is very much the subject of Riding the Midnight Express, a thrilling firsthand account of his much-publicized prison break.

Audiences are most likely to know Hayes' story from the 1978 Oliver Stone film Midnight Express, which was based on Hayes' book of the same name. As Hayes will tell you, the film is based on his story, but it takes a lot of liberties. Most notably, this speech earned Hayes a 20-year Interpol arrest warrant issued by the Turkish government. (Turkish law is notoriously sensitive to perceived insults.) But Hayes never actually said a word of it. It was written entirely by Oliver Stone.

Hayes sets the record straight in this no-frills solo show, which feels more like listening to a fantastical story at a cocktail party than it does watching a show onstage. Armed only with a cushioned stool and a bottle of water, Hayes tells his audience what life was like in a Turkish prison circa 1971: smelly. While the film depicts a dimly lit and sprawling Turkish bath for its famously erotic "shower scene," Hayes lets us know that hot water was available for only one hour each week, and inmates were forced to crowd around a big stone sink in the prison kitchen and douse themselves with water from a plastic jug. Oh, and they had to keep their underwear on. Sexy? Not so much. While the film makes it clear that there is no sexual contact between men in the prison (just lots of sweaty, longing gazes), Hayes reveals in his monologue that he actually had an intimate relationship with a Frenchman while he was locked up.

Hayes' original sentence of four years, two months was elevated to a life sentence upon retrial (also part of Turkish law). According to Hayes, the high court in Ankara was "responding to Nixon's War on Drugs and wanting to set an example." That's when he began to plot his escape in earnest. I'll say no more about that, but it suffices to say he lived to tell his tale to an off-Broadway audience.

It is fascinating to hear the now-graying 66-year-old Hayes talk about his much younger self. He's clearly lost none of his spunk and flower-child spirit, although he's arguably wiser from the experience (not to mention fluent in Turkish). Still, his delivery is oddly detached and performative for a man talking about things that actually happened to him. It feels a lot like watching an amateur actor (which Hayes is) in a community-theater production of someone else's solo show.

Thankfully, we're spared any exaggerated Turkish accents or uncomfortable audience interaction. It's just Hayes and his story up onstage. And he has a truly interesting story to tell. Do yourself a favor and stick around for the Q&A session right after the monologue ends. The theatrical front immediately drops and Hayes magically turns into a real and quite charming human being.