Should Kristin Chenoweth Play Paul Robeson? (Part II)

Ethnicity, gender, and the complexities of casting.

This is part II of Michael Feingold's latest "Thinking About Theater" column. Click here to read part I.

After World War II, an eager crop of gifted young African-Americans, college-educated and classically trained, flourished in theaters and opera houses, knocking down antiquated racial barriers. By the time I came to New York, in the early '60s, it was normal to go to the Metropolitan Opera, for example, and see Leontyne Price and Rosalind Elias playing the sisters in Mozart's Cosi fan tutte, or to head for the Delacorte, where the best Claudius and Gertrude ever, James Earl Jones and Colleen Dewhurst, confronted Stacy Keach's Hamlet. And as for Lorraine Hansberry's question "Who ever said Queen Titania was white?" the Yale Rep answered it triumphantly in 1975 with a Midsummer Night's Dream featuring the extraordinary Carmen de Lavallade, still incandescent in my memory as the most magical of all Titanias (and still luminous today at 83).

The tricky part — there's always a tricky part to these matters — comes after redress has been achieved to some degree. Though nobody had ever said Queen Titania had to be white, other classic roles suddenly seemed ethno-specific, through an updated political awareness that didn't always jibe with the text being reconsidered. Caliban in The Tempest, for instance, has in recent decades often been "typed" as an African-American role, viewed in the light of postcolonial experience. But Caliban's not a native victim of colonialism — he and his mother, Sycorax, were invaders who took over the island, just like Prospero.

Specificity can shed sudden new light on a familiar play: I remember an Othello off-Broadway, decades ago, in which the beauteous de Lavallade played Emilia to the Othello of Earle Hyman and the Iago of Nicholas Kepros. The vague flicker of motive that Shakespeare gives Iago — he suspects that Othello may have slept with his wife — suddenly leapt out in bold relief, giving what had always seemed mere words a startling plausibility.

Even greater, for me, was the pivotal moment seized by James Earl Jones when the Public Theater produced The Cherry Orchard with an all-black cast in 1972. There was no attempt to shift the play's historical setting, or to Americanize it. But the moment inevitably came when Jones, as Lopakhin, stepped into the parlor, looked around, and said, "My grandfather was a slave on this plantation, and now I own it." That statement needed no explanatory context to resonate with an American audience, especially when made by an actor of Jones' stature and projective power.

The strength of such instances affirms the complexity of the issue. Clearly, nontraditional casting offers multiple ways to proceed: ethno-blind (anybody can play anything); ethno-correct (whites play whites, blacks play blacks, Asians play Asians); ethno-aware (nonwhites play nominally white roles to which their presence adds an extra dimension). I know an actress of color who aspires to be the first female African-American King Lear. And why shouldn't she, in an age when so many men have played Lady Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest that casting a woman in the role now seems positively avant-garde?

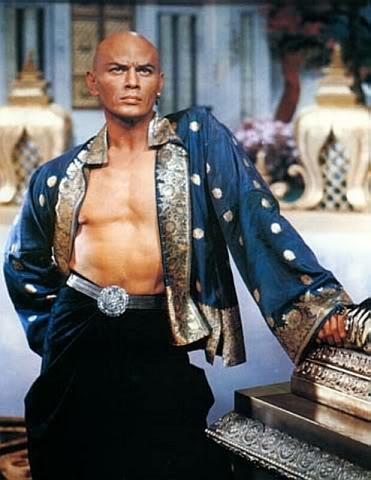

Sorting out what constitutes equality, fairness, or common sense can often turn knotty. In one recent instance, Dallas Summer Musicals has had a struggle over its current production of The King and I. The historical King Mongkut of Siam was manifestly Asian; Yul Brynner, who created the role on Broadway in 1951 and became identified with it through the film version and innumerable stage revivals, just as manifestly was not.

Yes, today this seems inappropriate, and the role is most often, though not always, given to an Asian-American actor. (In the current New York production of The King and I at Lincoln Center's Vivian Beaumont Theatre, the role is played by Ken Watanabe.) DSM hadn't set out to cast a non-Asian; several Asian-Americans on its callback list couldn't commit to their availability because they were on hold as possible understudies for the Lincoln Center production, which began performances on March 12. So DSM cast a Caucasian, duly received protests from the Asian-American community, and in response rethought its position, apologized graciously, searched a little harder, and found an Asian-American performer — already known to them — well qualified for the part. Happy ending — albeit at the cost of a little extra effort, expense, and discomfiture. Not the worst story of its kind.

(© Joan Marcus)

Yet it leaves me wondering: Suppose DSM had turned the issue on its head, by sticking with the white guy and casting an Asian-American soprano as Mrs. Anna. If the King must now always be non-Caucasian, must the lady always be Caucasian for dramatic contrast? My theatergoing experience suggests that gifted Asian-American actresses who could sing this role are not in short supply.

I realize, of course, that our culture has not yet advanced to the point when a minority that has seen itself displaced and caricatured onstage for decades would readily relinquish what might be called its proprietary rights in an ethnic role. Still, there seems a flicker of unfairness in the idea that while the King must be Asian, and Anna may be Asian, actors of stature whose DNA is sorted differently need not apply.

As a critic, I feel uncomfortable about that: I don't insist on seeing either an Asian or a non-Asian actor play the King; I want to see the actor who will embody the King most convincingly and most memorably. And I want to believe that we are at least approaching a time when that will occur without reference to the actor's offstage identity. So in answer to the question asked by my annoying headline. No, I don't really think that Kristin Chenoweth should play Paul Robeson. She's too short for the role, and besides, she's busy elsewhere. Instead we will have to see what Daniel Beaty makes of Robeson at BAM in The Tallest Tree in the Forest. But I do look forward to a time when nobody feels threatened or offended by the notion, and the only question involved would be how movingly Chenoweth could or couldn't sing "Ol' Man River."

That time won't come, I realize, until we've passed through our current period of redress, and made reparation for the systematically unjust miscastings of the past. But that new time feels imminent, clashes like the King and I incident notwithstanding. It felt close to me at the Public Theater when I saw Lin-Manuel Miranda's new musical, Hamilton. Here was American history, cogently and imaginatively written in a contemporary pop-rap form that invited youngsters in without pushing people my age out: fusion.

Hamilton's cast is black, Latino, white, and Asian: fusion again. The cast's ethno-coding is sometimes used to underscore differences — Alexander Hamilton (Miranda himself) Latino, Aaron Burr (Leslie Odom Jr.) black — and sometimes to emphasize their irrelevance: Hamilton's wife, Eliza (Philippa Soo), is Asian-American; her sister, Angelica (Renée Elise Goldsberry), African-American. And the casting can supply its own comment: What we know about Thomas Jefferson gives an extra comic edge to the presence of Daveed Diggs in the role, his extravagant Afro shooting out in all directions. In the midst of the whirling frenzy, on comes Jonathan Groff (replacing Brian d'Arcy James) as George III, practically stealing the show with sly, understated irony.

This is America, and this is casting today — not as the literal-minded defenders of either old conventions or their modern correctives see it, but as our hope for an equal and just America wills it to become. Undoubtedly we will stumble over one another many times, and get into many irritable arguments, before it is fully achieved. But we can dream of it as we press forward, the theater being, anyway, only a place where we dream together as a community.

Michael Feingold's next "Thinking About Theater" column will appear in June.

Michael Feingold has twice won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism, most recently in 2015 for his "Thinking About Theater" columns on TheaterMania, and has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism. He serves as chairman of the Obie Awards and has also worked as a playwright, translator, and dramaturg.