Describe the Night

(© Ahron R. Foster)

Are you disturbed by the never-ending assault on reality in contemporary America? If so, don’t bother complaining to a Russian about it. You’re likely to get a shrug in response: In Russia, you don’t know the truth; the truth knows you. Belief precedes evidence and everyone is entitled to his own version of the facts. Rajiv Joseph weaves a compelling narrative from the yarn of bespoke reality in his latest play, Describe the Night, now playing at Atlantic Theater Company. It’s the kind of historical revisionism that is thrilling onstage, but deadly in government.

Like a conspiracy theorist drawing arrows on a chalkboard, Joseph attempts to connect three major stories from the last century: There’s the tale of author Isaac Babel (Danny Burstein), who meets lifelong friend and future secret police chief Nikolai Yezhov (a brutally funny Zach Grenier) while serving in the Red Army in 1920. Then there’s the story of inscrutable K.G.B. officer Vova (a menacing Max Gordon Moore) and his obsession with Urzula (Rebecca Naomi Jones), the Dresden woman he is assigned to surveil in the twilight of Communism. Could Vova know the truth behind our third story? It takes place in 2010, after a plane carrying most of the Polish government crashes in the woods outside of Smolensk, killing everyone on board. Assigned to cover the Polish delegation’s visit, Russian reporter Mariya (Nadia Bowers) seeks refuge in the car rental office manned by Feliks (Stephen Stocking), fearing that she will be arrested in a roundup of journalists.

(© Ahron R. Foster)

Some of these characters are real and some are invented, and unless you are an expert in Russian history, you may not immediately know which is which. Adding to the intrigue, these three stories are linked by an enchanted book and a character named Yevgenia (Tina Benko). Benko plays her with witchy relish, endowing this witness to the entirety of the 20th-century with furtive power. “There are no more dreams,” she accosts Vova as much as she warns us, “and there is nothing but war ahead!” It’s enough to make the hairs on the back of your neck stand at attention.

Benko frightens us, but Burstein breaks our hearts. Babel emerges as a figure of resistance to authoritarian oppression, asserting the indomitable human spirit with playful wit and inexhaustible compassion. No one is better suited to play that role than Burstein, whose fearless sincerity makes us believe that Babel is really in the room with us.

(© Ahron R. Foster)

Earnest performances are a key ingredient in the magical realism that Joseph and director Giovanna Sardelli impressively sustain for nearly three hours. At one moment, it feels like we’re watching a historical drama, but then a file drawer extends across the stage, or three people sit down for a meal of leech soup, and we realize that something is slightly off. But just because an aspect of the story has been exaggerated, does that make the whole thing untrustworthy?

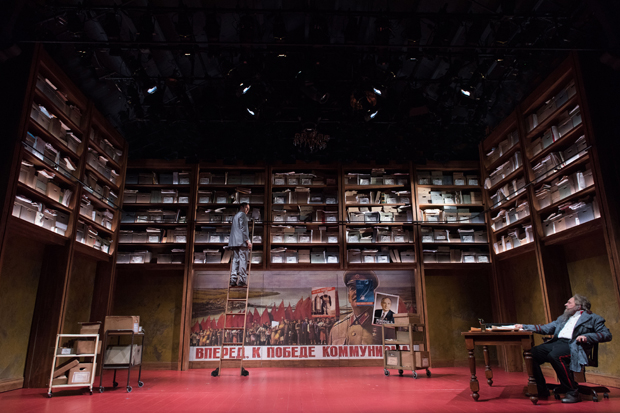

In mixing this potent cocktail of fact and legend, Sardelli delivers an arresting production that often makes us feel like we’re in a Russian theater: Her use of music (haunting original work by Daniel Kluger) is reminiscent of the Vakhtangov under Rimas Tuminas, while her strategic employment of jaw-dropping stage pictures conjures the work of Dmitry Krymov. Tim Mackabee’s set is an open space in which Sardelli can fit nearly a century of plot. The action seems to spring from the tall towers of file boxes that overlook the stage. Amy Clark’s costumes and Leah Loukas’s wigs help clarify the time period while allowing for seamless transitions in a disjointed timeline. Lap Chi Chu’s lighting ranges from aggressively realistic to highly fantastical. Disarmingly, the journey between the two often happens without us noticing.

Joseph has trafficked in dubious history before, notably in his last play at the Atlantic, Guards at the Taj. Describe the Night feels like the next frontier, a spacewalk into the “culture of zero gravity” described by journalist Peter Pomerantsev in Nothing Is True and Everything Is Possible: The Surreal Heart of the New Russia. That book is an account of what happens to a country when the public discourse devolves into a delirious hopak of feelings and fiction. Describe the Night is much more than an engrossing tall tale, however: It heroically wrestles with the slippery nature of truth itself, and unnervingly demonstrates why its alternatives are so seductive.

(© Ahron R. Foster)