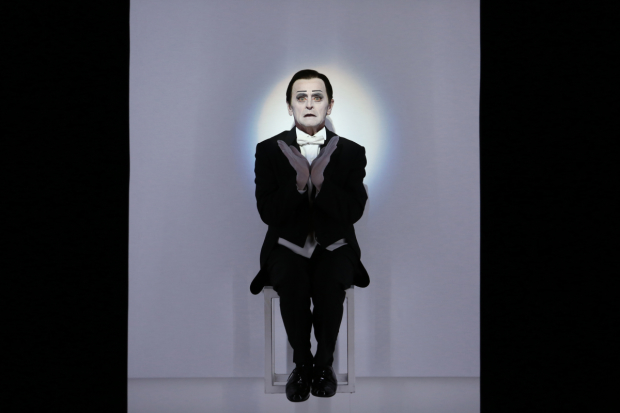

Letter to a Man

(© Julieta Cervantes)

In 1919, Ballets Russes star Vaslav Nijinsky decided to document his deteriorating mental state in a diary, recording his thoughts as they came to him. Nijinsky's stream of consciousness makes for compelling, opaque, and occasionally frightening reading. While his dancing has sadly been lost to history (not a shred of film exists), Nijinsky lives on through his reputation and words. Auteur director Robert Wilson has now turned the diary into Letter to a Man, a new solo show starring Mikhail Baryshnikov (who also appeared in Wilson's The Old Woman at BAM in 2014). Unfortunately, this collaboration of exciting artists tackling a fascinating subject lands at BAM's Harvey Theater with a disappointing thud.

Undoubtedly, seeing Baryshnikov (the greatest dancer of his generation) portray Nijinsky (the greatest dancer of his) is a must-see event on its own, making Letter to a Man worth it right out of the gate. It's an added bonus that the instantly recognizable Robert Wilson directs. While Wilson's style of controlled movement and textual repetition seems particularly suited to Nijinsky's short, declarative (and often redundant) sentences, the stage treatment never really reaches beyond the superficial. Wilson is unable to unlock the internal logic of the man's madness, making this feel like a missed opportunity.

(© Julieta Cervantes)

Make no mistake: That logic definitely exists. Written in Switzerland at the tail end of World War I, Nijinsky's diary conveys the drama of a man who is aware of his mental illness, but who is furiously struggling against it. He is also fighting to make sense of a world that, itself, seems on the precipice: British Prime Minister David Lloyd George and American President Woodrow Wilson are characters in this drama as seemingly familiar to the author as Sergei Diaghilev (his former employer, lover, and the unnamed "man" of the titular letter) and his wife. Sexual and religious obsessions further color Nijinsky's language, leading to almost prayer-like blocks of text: "I am God's plan, and not the Antichrist's. I am not the Antichrist. I am Christ."

Wilson captures the rhythm of the text through audio recordings of Baryshnikov reading Nijinsky's words in English and Russian (faithful textual adaptation by Christian Dumais-Lvowski): "I understand war because I fought with my mother-in-law," he repeats several times at the top of the show while confined to a straitjacket.

At one point, Baryshnikov runs toward the upstage wall only to be caught in a hailstorm of machine-gun fire (disturbing 360-degree sound design by Nick Sagar and Ella Wahlström), inexplicably repeating this motion several times like a video gamer hitting reset. Despite the specter of death hovering over the stage, the stakes feel shockingly low.

Some of this might be explained by Wilson's decision to begin the story in 1945, two decades after Nijinsky stopped writing. The stage action is meant to convey Nijinsky's endless dance with his ghosts "behind the silence" of the man in the straitjacket. We are always aware that he has long ago surrendered to his madness, and everything we are witnessing is just a rehash of the battle he lost 26 years earlier.

(© Julieta Cervantes)

In lieu of dramatic tension, Wilson at least treats us to his typical dosage of visual stimulation. A cardboard cutout girl leads a giant chicken across the stage as white flowers descend from the fly system. Later, the performer (or a very realistic mannequin) appears suspended upside down in a Wilsonian box of light that changes hues with each recitation: "I am not Diaghilev. I am not Diaghilev," the voiceover repeats. In the most beautiful stage picture of the evening, Nijinsky peers out an arched window that provides the only source of light onstage (gorgeous and flawlessly executed lighting by A.J. Weissbard). One imagines the snowcapped Alps beyond as he languishes in his cell.

Baryshnikov is the ideal performer for a director like Wilson, who demands rigorous specificity in every detail. His graceful and arching limbs make each movement a line of poetry. His ability to sharply change shape or facial expression with the sound and lighting helps to maintain the visual perfection of Wilson's creation.

(© Julieta Cervantes)

Unfortunately, extended transitions that have the audience staring at nothingness seriously undermine any tension built up by the design and movement in the previous scene. Tongue-in-cheek musical tracks (like Napoleon XIV's "They're Coming to Take Me Away, Ha-Haaa!") that play during these breaks don't help matters. In the final scene, Nijinsky appears self-satisfied and completely at peace. This feel-good ending comes completely unearned, like a false epiphany to a much sadder tale. We never entirely believe the happy ending, which might explain the beat of confusion that occurs after the house lights come up, but before the audience finally claps.

None of this will do anything to disappoint those looking to see Baryshnikov live: He's at BAM and he's magnificent. Sadly, those looking to illuminate the century-old mystery of the brief career and extended madness of Vaslav Nijinsky will have to wait for another play.