Judith Malina and the Award-Season Rush (Part II)

This is Part II of Michael Feingold's latest "Thinking About Theater" column.

Click here to read Part I.

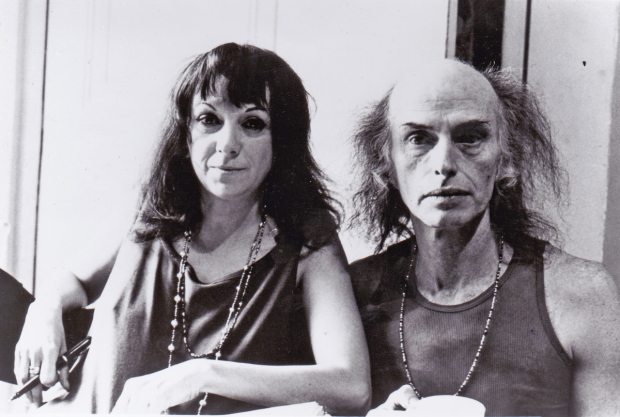

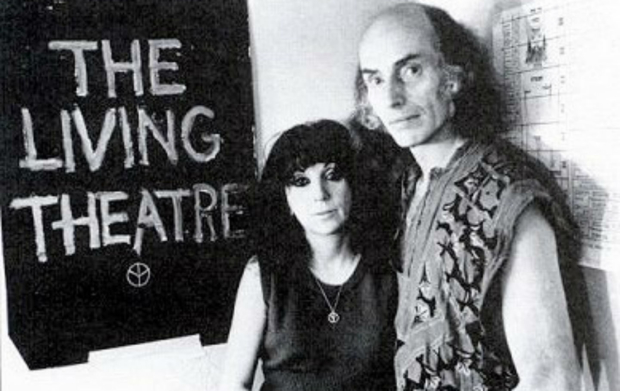

The late Judith Malina, who died on April 10, just as Broadway was gearing up for its vast outpouring of new productions in advance of award-nominations deadlines, was a hero to many theater people, myself included, but the word "exemplary," which some have applied to her life, makes me slightly uncomfortable. An exemplar is someone whose life can serve as a model — literally an example — to others, and I'm not sure that I would like to see large numbers of young theater people trying to duplicate what Malina did. The passionate consistency of belief, both aesthetic and political, that made her an inspiration (the correct word) to so many of us also led her into a chronicle of sufferings, mingled with triumphs, too long and harrowing to detail here.

In addition to the Living Theatre's travails with the IRS, mentioned in Part I of this essay, the company's New York life was marked by periodic conflicts with the Buildings Department. Its wandering years in Europe, and later in Latin America, were marred by violent incidents, political crackdowns, deportations, arrests, and jail time, with all the attendant brutality those terms imply. Within the joy of their creative endeavor, Malina and other members of the troupe suffered much for the sake of their total commitment to their belief. That the joy continued, and ultimately won out, is more a tribute to her indomitable spirit than a vindication of her principles.

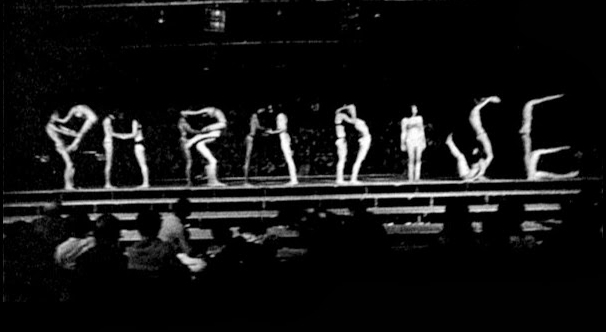

Anarchism, pacifism, poetry, and parable summed up Malina's credo as well as her methodology. The gigantic, free-form creations that the Living Theatre brought back from its European exile in 1968, Frankenstein and Antigone (the latter, Malina's translation of Brecht's adaptation of Sophocles), seemed to have exploded from the taut confinement of The Brig. They were the spiritual equivalent of a prison break — one in which, with the open-work structure of their next piece, Paradise Now, they effectively invited the audience to join them.

While embodying deep conviction, these pieces also showed a surprising lightness of heart. You might expect people who preach Anarchism to be earnest; in Paradise Now, the Living Theatre spelled the word out with their bodies, like acrobats on a "Visit Florida" postcard. Malina's pixilated performance in the title role of Antigone challenged Creon's totalitarian menace with flashes of childish teasing, which made the ultimate tragedy seem that much more terrifying. And the eerie scene in Frankenstein of the Creature's social conditioning built to a frenzy of mental circuit overload from which it escaped by sliding headfirst down a pole at the center of the three-story set, landing amid a chorus of women who welcomed it by singing Shakespeare's "Full fathom five" to the tune of the "Ode to Joy" from Beethoven's Ninth Symphony.

Extravagant moments like these showed the kinship of Beck and Malina's vision to the eye-and-ear-dazzling art that makes audiences love Broadway musicals. But there are two key differences: First, the Living Theatre's work was always conceived and built on a "poor theater" budget. Its intent was not to impress audiences with the lavish outlay of money spent — what the economist Thorstein Veblen long ago baptized "conspicuous waste" — but with the lavish outpouring of the human spirit that a theatrical collective could produce. Second, Malina and her troupe never tailored their ideas, political or otherwise, to the audience's conventional expectations; rather they challenged and encouraged the audience to come forward and meet their ideas (often much harder to swallow than their imagery). Those who accepted the invitation, after performances of Paradise Now and many pieces that followed, often became participants themselves, engaging in activities very different from the carefully regulated Broadway modes of interactive theater.

That pair of differences — Judith Malina's notion of the means and the motives of theatermaking vis-à-vis Broadway's — is what makes the image of her death arriving amid the flood of glittery uptown openings stand out for me.

Malina was neither immune to nor ignorant of commercial ways. In fact, we owe her extensive filmography to the eerie symbiosis that she practiced with film and television producers: They offered her roles because she was a distinctive personality as well as a skilled actress; she took them on, without shame, as a means of subsidizing the theater she believed in. That one of the leading figures of radical-protest theater can be seen raising a street ruckus as Al Pacino's mother in Dog Day Afternoon (1975) perhaps constitutes a witty stroke of casting. That she can also be seen as Granny in The Addams Family (1991), as a dying nun with a secret on The Sopranos (2006), in a dozen other feature films, and on episodes of ER and Miami Vice simply demonstrates a hardheaded radical's cost-accounting procedures: "Let the establishment subsidize me," she said in effect, "I will use their money to alter their world."

Malina could take this stance in part because she was, quite simply, fearless, and in part because her fearlessness drew some of its strength from the world in which she had come of age: Artists from every field communicated; it was not unnatural for the poets and painters, among whom the Living Theatre grew, to go see a Broadway show, nor for an actor to turn up at a poetry reading or a new-music concert. That world also understood artists as, to some extent, outsiders who might take a critical stance toward every aspect of contemporary life.

Reeling from Broadway's April rush to beat award-nominations deadlines, I thought of the poet and film critic James Agee — who, as it happened, had been one of Malina's lovers in the 1950s. When Agee was faced with the flood of film openings that preceded every holiday season, he bunched them together, under headlines like "Midwinter Clearance," jabbing each unimportant film with a sharp, stinging one-sentence review: "When this film was made, Betty Grable was in an early stage of pregnancy; everyone else involved was apparently in a late stage of paresis." "Several tons of dynamite are set off in this picture, none of it under the right people." And most memorably, of an overblown 1948 musical called You Were Meant for Me: "That's what you think."

Theater critics — Eric Bentley and Kenneth Tynan come to mind — have practiced that kind of condemnatory, intellectually provocative terseness. But today both theater and film have become such corporatized enterprises that the effect would cause not only shock but also active offense. In art as everywhere else, the moneyed bigwigs who increasingly run the world do not care to see their actions criticized. Judith Malina did not hesitate to criticize the way our world is run, and she spent her life finding creative forms in which to encase her critique. Though I found many things to enjoy in the pileup of openings that temporarily blocked her death from my consciousness, I believe I would trade almost all of them to have working again, at full strength, the critique she embodied of our entire system.

Michael Feingold's next two-part "Thinking About Theater" column will appear on consecutive Fridays July 24 and 31.

Michael Feingold has twice won the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism, most recently in 2015 for his "Thinking About Theater" columns on TheaterMania, and has twice been a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Criticism. He serves as chairman of the Obie Awards and has also worked as a playwright, translator, and dramaturg.