Barry Bostwick and Carole Demas Take Us Back to a Time When Grease Wasn't Necessarily the Word

As Grease celebrates the 50th anniversary of its Broadway premiere on Valentine's Day, it's worth remembering the musical's earliest days, before it became such a phenomenon.

First seen in a down-and-dirty production at Chicago's Kingston Mines Theatre in 1971, Grease's 1972 New York premiere at the Eden Theatre on Second Avenue wasn't particularly auspicious. The authors had no previous Broadway writing credits, the cast was unknown, the director had no Broadway experience, and the producers had previously produced only a single Broadway play. The raunchy Chicago version had been significantly revised for its Manhattan debut.

Initial reviews were mixed, with Clive Barnes writing in the New York Times that, "The music is the loud and raucous noise of its time. It is meant to be funnier than it is." Also writing for the Times, Walter Kerr was more generous, saying Grease was "a mostly agreeable musical about the very last moment in time when boys submitted to haircuts." But it wasn't an immediate smash, with producer Kenneth Waissman suing Variety at one point for writing that the show was playing to only 30 percent capacity in its early days, when he said it was doing a not exactly stellar 60 percent.

Yet Grease found its fan base, and by the time it closed after an eight-year run, it was the longest-running Broadway show in Broadway history (for a time). The 1978 film was a smash, the No. 1 film of the year, surpassing the runner-up, Animal House, by some $40 million in box office grosses. The film's soundtrack album was number one on the Billboard charts for 12 weeks.

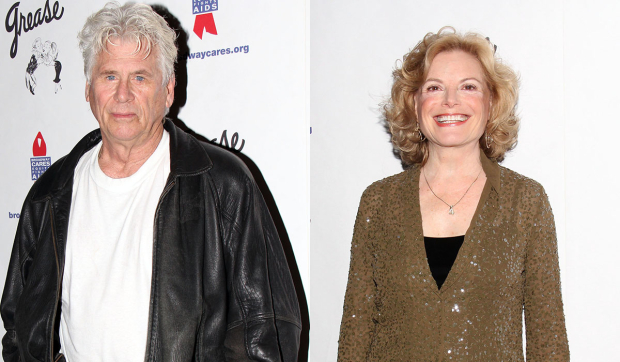

Speaking just a few weeks before Grease's Broadway anniversary, the original Sandy and Danny— Carole Demas and Barry Bostwick — recalled the stage origins of the now-classic musical.

(© Tristan Fuge)

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

What do you remember about the overall approach to portraying the 1950s in Grease?

Barry Bostwick: The take was we tried to be as reverential and true to what the period was. But we also knew that it was an entertainment. So it had to be slightly larger than life. We would take gestures and phrases and explode them a bit.

Carole Demas: It felt very genuine to me. One of the things I remember, just in terms of the craft of theater, was that [director] Tom Moore, who was miraculous, had to balance between creating a show that would be acceptable to families, to the matinee crowd, and still manage to keep the grit, the actual reality of these people. I think the reason that it works so well was that every single one of us was so totally invested in the reality of our character, that you sat there and you laughed, but you also cried. You felt that teen angst.

Barry: We were all products of the late '50s. So we had in our memory banks the sound and the feelings of what those songs did to our emotional lives, and how they were the soundtrack for our high school memories. I don't think that we were quite as rough, and really over the top with the music, as the play progressed over the years. It just got sillier and wider and bigger and more caricature-y. I think that we were still somewhat playing the real characters. Even though we were too old to be playing them, I think there was an honesty to the piece that over the years has lost its teeth.

Were there a lot of changes happening with the material while you were in rehearsal in New York?

Carole: It was difficult for Jim and Warren to give up some of that grit. Because it was the core of it all for them. Tom Moore had a vision, and a good sense about what would work on Broadway, what would be acceptable to an audience. He wasn't trying to whitewash it. My perception of what I saw going on was that he didn't want to lose that basic, tough core of these kids, and the pain, a lot of them were in. But he didn't want the language to shock or stun in a way that that turned people off. Yet Jim and Warren knew that that was the truth.

Barry: It was like a typical musical that we all had been involved in; most of us had tried to get into a production of Hair or other rock musicals at the time. I think we added an energy. That was irreplaceable. But I don't think we added a lot of content.

Grease was not immediately greeted with raves, and it was not selling out early on. Do you remember when it turned into a hit?

Barry: It was a slow grind. It was very similar to The Rocky Horror Picture Show. It was discovered by people who would come back again and again or bring other people. I just remember opening night. My father came to New York from California. And I think on the way home to our loft down on the Bowery, he said, "You better start looking for a new job." Because he didn't… he didn't think it was any good. I certainly over the years made him eat his words on that.

Carole: All of us remember opening night at Sardi's when two reviews came through, and neither of them was very good. They didn't get it. I think critics didn't know quite what to do with it. When we moved to the Broadhurst, a writer named Harris Green wrote a huge article with a picture of Barry and me at the drive-in about Grease, which said a lot of things that were very positive. He really got it in a way that it wasn't quite viewed early on.

Recent versions of the show no longer include the songs "Alone at the Drive-In Movie" and "All Choked Up." How did those work in the show?

Carole: "Drive-In Movie" was a tour de force for Barry. He sat there, you know, on that car heartbroken. But I think a lot about whether it worked or not depending on who was playing Danny and how it was delivered.

Barry: "Alone at the Drive-In Movie" was replaced by "Sandy," the song in the film. I think it's because it was so specific and tongue-in-cheek, a takeoff on a particular genre of song of the time. It might have been too much of an inside joke. I think I understand why it wasn't in the movie, because they needed to give John a real moment of stardom, of sexiness, of anguish.

Carole: "All Choked Up" really was a story song, explaining, from Danny's point of view primarily, how he how he felt about seeing Sandy pull this off, and Sandy standing her ground and telling him off. A lot of people had a great time with that.

Barry: I never liked "All Choked Up." I think I wish they had written "You're the One That I Want." I found it a struggle. I just didn't think it was powerful enough for that moment for her to come in make and make that change. I was trying to pull every stop I could to make it interesting, and I think get beyond what I felt the song lacked.

Can people enjoy Grease the same way they did 50 years ago?

Barry: I would love to see it onstage with real teenagers that had talent. Even the version on television didn't have that naïveté and bravado that I think we tried to bring to it.

Carole: I don't love when the whole thing becomes very cotton candy, bubble gum really, because it seems to take away some of the significance of the show for me, just becomes a lot of fluff. You can see how it lends itself to that. But one of the things I talk about with the kids that I work with sometimes is that these kids feel all the things you feel, but they aren't exactly you because they don't, they didn't have what you have.

Barry: I don't know if you can do that because high school kids today don't have that kind of innocence and complexity of simple emotions. But that's just my theory.

Carole: A teenager's a teenager, even in this world of social media and whatever, where they're walking around, bumping into each other looking at their phones. They still want to wear the right thing and say the right thing. They still have the same fears, they still have the same longing, we still have that same sexual pull, when they see each other.