America's Greatest Woman Playwright (Maybe) (Part II)

Listening to Ruth Draper, actors and playwrights learn simple truths.

This is part II of Michael Feingold’s latest “Thinking About Theater” column.

Click here to read part I.

Throughout her decades of theatrical success, Ruth Draper (1884-1956) retained one key trait from her upper-echelon upbringing: her privacy. She shunned, for most of her career, photographers and interviewers. Russell Crouse, who briefly handled her publicity in the years before he and Howard Lindsay became one of Broadway’s star playwriting teams, complained that “she didn’t want any publicity… Everything I did to help her sell out, which she did, I did in spite of her.” Her entire filmography consists of two brief TV appearances from the time of her farewell tour, neither currently accessible online.

But the kind of loyalty that Draper’s artistry built in fans and colleagues can become productively addictive. Charles Bowden, who coproduced Draper’s last Broadway appearances, finally coaxed her into an RCA Victor recording studio; the label’s star conductor, her friend Arturo Toscanini, offered his engineer’s services. Knowing Draper’s perfectionist bent, Bowden made the engineer keep the tape running during her preliminary run-throughs, preserving 25 pieces, a good chunk of her repertoire. Cautious RCA then issued a single disc containing three items: “The Italian Lesson,” “Three Generations in a Court of Domestic Relations,” and “A Scottish Immigrant at Ellis Island.”

And that was all the Draper you could get, between her death in December 1956 and the mid-’60s, when RCA leased the rights to a small label called Spoken Arts, which reissued the first LP and added four more, for a total of 11 pieces. These, passed from hand to hand or duped on cassette, became the basis for a sort of Ruth Draper cargo cult. Almost every actor, director, or playwright I questioned for this essay had first encountered her through these LPs, most often only through the very first one — and often remembering from that one just “The Italian Lesson.”

Even among solo performers, Draper became a virtual trade secret to be handed on. Charles Busch, who spent seven years creating solo pieces before he ventured into traditional playwriting, stumbled on Draper’s name in an interview given by Lily Tomlin, a fierce devotee. Solo performer and actor David Cale heard the LPs at the urging of his colleague Emmett Foster, whose Emmett: A One Mormon Show borrowed the structure of Draper triptychs like “Three Generations.” Doug Wright, author of the Pulitzer-winning solo play I Am My Own Wife, listened to Draper at the behest of performance artist John Kelly.

(courtesy of Everett Collection)

Martin Moran, creator of the conscience-troubling solo The Tricky Part, met “The Italian Lesson” via actor Keene Curtis; David Grimm, author of last season’s Tales of Red Vienna, thanks the Houston-based actress Annalee Jefferies for his introduction. Director Mark Brokaw learned of Draper while watching actress Patricia Norcia, who for several decades made a small cottage industry out of re-creating Draper performances. And significantly, Busch’s frequent acting partner Julie Halston heard Draper for the first time in a college language lab, where her pieces were used as models for the pinpoint accuracy of her accents.

Which brings us to writer and editor Susan Mulcahy. In the late 1980s, a friend who taught Italian shared with her a tape of — what else? — “The Italian Lesson.” Mulcahy’s fascination soon became a merger of Tomlin’s devotion with Bowden’s persistence. She pitched Draper for a 1999 Vanity Fair article, now being evolved into a book. More importantly, she led a crusade to make Draper’s work more accessible than ever, negotiating a contract with BMG, which had subsumed RCA, to issue the recordings on CD for the first time, marketing them chiefly through www.drapermonologues.com. The two dual-CD sets thus far issued contain 17 of the 25 pieces Draper recorded, including, for the first time, the spectacular “In a Railway Station on the Western Plains,” the piece that had made Woollcott rave about Draper’s humanitarian outlook back in 1921.

Six minutes shorter than “The Italian Lesson,” this remarkable piece makes a stunning contrast to it. Instead of a giddy society lady struggling with servants and appointments, the speaker of “In a Railway Station” is an ordinary homespun woman, working the night shift at the station café, dealing first with the few workmen who pass by on a snowy night, and then suddenly, traumatically, confronted with a flood of injured passengers rescued from a train wreck. While the events spin increasingly out of control, the speaker shows her brains, compassion, and resourcefulness, successfully keeping calm while enduring the severest test of her life. The content may be pure disaster-movie stuff, but Draper’s exactitude, getting its full emotional value while dodging histrionic excess at every step, makes most such movies seem garish embarrassments by comparison.

This isn’t the only piece that dramatizes Draper’s democratic sensibility, her sharp awareness of disparities in class and temperament. Though her rich women are, often, a little sillier and more self-centered than those below them in status, they’re equally granted their own point of view, their own skill at coping with situations. Her eagerness to celebrate their individuality, perhaps, is what does most to keep her recorded monologues so fresh, even after many hearings.

(© David Gordon)

Draper did not invent solo performance. There were monologists before her, like Beatrice Herford, who presented “types” rather than characters. Vaudeville teemed with monologists who, like Cecilia “Cissie” Loftus, did celebrity impressions or, like the red-wigged female impersonator Bert Savoy, centered their routines on one stock character.

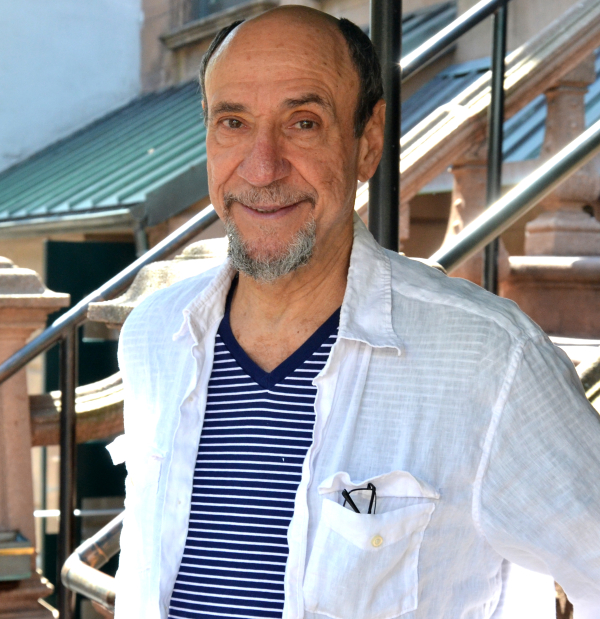

But none of them achieved Draper’s stature, or left behind a reputation to match hers. Rehearing her, it’s easy to see why: She neglects nothing and overemphasizes nothing. Every touch strikes deep, and strikes lovingly. Most important, she makes sure the touches add up to a total picture. “She was important to me,” says F. Murray Abraham, currently starring on Broadway in It’s Only a Play, “for helping me understand form. I think we often forget that what we do, as actors, is tell stories. That first became clear to me listening to this master storyteller.” No disagreement here: Put the disc in the drive, and Ruth Draper’s stories emerge, alive as ever.

Michael Feingold’s next two-part “Thinking About Theater” column will appear on consecutive Fridays October 24 and October 31.