The Tallest Tree in the Forest

(© Max Gordon)

"When you have the ears of millions, what do you say," Daniel Beaty asks in the opening moments of his tour-de-force solo play The Tallest Tree in the Forest. "What do you have a responsibility to say?" Contemporary celebrities (from Barbara Streisand to Mel Gibson) struggle with that question, but it was no clearer for previous generations. Case in point: the energetic and outspoken Paul Robeson, who is the subject of this NYC premiere from Tectonic Theater Project at BAM. It's an engrossing whirlwind journey through the history Robeson lived, and in some cases made.

Today, Robeson is best remembered for his starring role in the film adaptation of Show Boat, which he also performed on the London stage. His rendition of "Ol' Man River" has become the version against which all others are judged.

Beaty enters singing that iconic number, doing a convincing evocation of Robeson's booming vocals. He very quickly transitions to Robeson's early life as we discover that he wasn't always destined for show business. A graduate of Columbia Law School and Rutgers University (where he was the third black student ever), Robeson gave up his legal career for the stage when his golden throat became increasingly in demand among the Manhattan smart set. He wasn't so much part of the "talented tenth" as he was completely exceptional.

Beaty chalks much of that up to Robeson's ambitious father, a former slave (with a vaguely British accent) who teaches his son classical Greek and Latin while admonishing him to stay out of trouble. "Always show white people you are grateful," he tells Paul, before digging into Homer's Odyssey. Robeson's older brother Reeve takes a far more confrontational stance, fighting off a gang of white thugs who accost his little brother. With these two characters, Beaty establishes the conflicting impulses in Robeson's life: conciliation and militancy. It's a struggle that parallels the divergence of views in the larger African-American community (Booker T. Washington vs. W.E.B. Du Bois; Martin Luther King vs. Malcolm X). Beaty attempts to unpack how these impulses jockeyed for position within one man. This becomes an especially fraught process as Robeson begins to tie the fight for racial equality with class struggle, eventually landing in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee for his alleged Communist sympathies.

In attempting to capture the full breadth of Robeson's ideals, the creative team has constructed some real head-scratching moments, like a passage depicting Robeson's 1934 trip to the Soviet Union. Robeson and his wife Essie discover a land of racial harmony in which expatriate African-Americans prosper alongside their Russian brethren. They consider emigrating themselves before Robeson abruptly determines, "America is going to play a crucial role in the struggle against fascism that is to come. I want us to be there for that. We must go back home." This explanation feels rushed and all too convenient. One has to imagine Robeson had more complicated feelings about leaving what he describes as a "model of what America could become." At the very least, Robeson's Soviet comrades would have bristled at the notion that one must be Stateside to resist Hitler's Germany.

Beaty takes a fundamentally sympathetic view of his subject, but doesn't completely inoculate him from critique. Robeson's unwavering Stalinism (even as thousands of Soviet Jews were being murdered) comes in for a drubbing. Essie caustically asks her husband, "Paul, you have all that power. But how many Jewish people are going to die before you use it?"

Ultimately, Essie emerges as the story's most compellingly round character. She's the voice of Robeson's conscience, standing by her man even as he falls and simultaneously pursues her own academic career. Her swirl of contradictions feels entirely more organic than that of her husband. Luckily, Beaty doesn't give her short shrift, equally committing to the portrayal of both Robeson and wife.

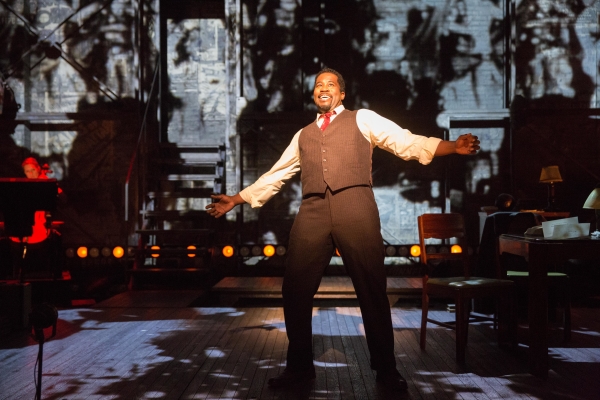

In fact, Beaty maintains a titanic presence throughout. With the backing of a stellar three-person band, he sings 14 numbers including a wall-shattering rendition of "Battle of Jericho" and melting-pot tribute "The Ballad for Americans." His rich and resounding baritone aside, Beaty convincingly embodies every character with a distinct dialect, posture, and facial expression.

Some of that can be attributed to director Moisés Kaufman, who achieved similar success with 2003's I Am My Own Wife, a solo play that won Jefferson Mays a Tony. Like in that show, the set of Tallest Tree (designed by Derek McLane) is dotted with the physical trappings of the subject's life: books, luggage, and so many microphones. John Narun's projections further illuminate the story with real photos, video, and propaganda posters from the era. Kaufman and Beaty have dug through Robeson's story with the meticulous precision of historians; they've thrown that copious research onstage with a classic sense of showmanship.

Improbably, the most memorable passage features Beaty portraying Columbia professor Jamal Joseph: "When you talk about race, there is a place for you in American history," he says, explaining why so much of Robeson's legacy has been obscured. "When you talk about class struggle, there is less of a place for you in American history. And if you talk about race and class struggle, then there's no place for you." In The Tallest Tree in the Forest, Beaty makes a strong argument that there should be a place for Robeson and his ideological successors.