Grand Concourse

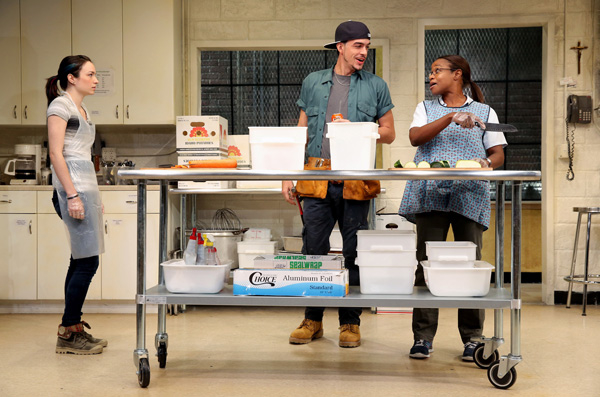

(© Joan Marcus)

The stage of the Peter Jay Sharp Theater at Playwrights Horizons has been transformed into a soup kitchen in the basement of a Catholic church in the Bronx. This is the setting for Heidi Schreck's Grand Concourse, a brutal response to the notion of unconditional forgiveness and never-ending charity. With its pointed perspective and merciless plot, Grand Concourse is likely to rouse flashes of anger and sadness. A master provocateur of a playwright, it's nearly impossible to walk away unscathed by Schreck's harrowing tale.

Sister Shelley (Quincy Tyler Bernstine) is a nun who has been running the soup kitchen for a long time. She chops zucchini like Martin Yan and serves an endless stream of needy mouths with the help of Oscar (Bobby Moreno), the church's Dominican handyman. Many of their visitors are regulars, like Frog (Lee Wilkof), a slightly unbalanced homeless man with a strange sense of humor. Shelley operates the kitchen with a rotating cast of volunteers. The newest one is Emma (Ismenia Mendes), a 19-year-old girl with an impulsive nature. In fact, her newfound volunteerism seems to be one of her whims.

"I thought it would help," she tells Shelley about her reason for joining the kitchen. It's not clear if she means she's offering help, or that she needs help herself. "I was hating myself and I thought maybe if I changed my hair I wouldn't notice it was me," she nonchalantly tells Oscar when he inquires about the My Little Pony-esque streak of color upon her head. "Ok so you're crazy," Oscar replies.

He's no psychologist, but it becomes painfully apparent that everyone (Oscar included) should have heeded his initial diagnosis. We can see Hurricane Emma coming from a mile away. That foresight makes it even more devastating when our most cynical prejudices are confirmed as Emma rips up the fragile ecosystem of the soup kitchen. You may feel the need to shake this needlessly needy girl and shout, Effie, we all got pain. Her amazing self-pity is made even more galling against the backdrop of the tidal wave of real desperation flowing in from the surrounding Bronx — New York City's most impoverished borough.

This strong reaction is most certainly amplified by Mendes' subtly muscular performance. She turns on real tears and exudes genuine vulnerability while playing a not-very-sympathetic character. She stomps around the kitchen to the sounds of Le Tigre, dramatically talking about what a "piece of sh*t" she is. "HELP ME," Emma screams at Shelley, prepared to detonate a truckload of guilt if the reluctant nun doesn't comply. Emma is an emotional terrorist.

As the jaded, no-nonsense Shelley, Bernstine plays a compelling foil. She convincingly portrays a nun struggling with her faith and a serious case of midlife ennui. Praying in front of the microwave (which she uses to time her talks with God) she ventures, "Justice for immigrants," before wincing at the hollowness of her own words. Still, Bernstine never lets us forget the pilot light of optimism that flickers beneath Shelley's layers of armor; this makes us root for her.

Sporting a backward Yankees cap and messy chinstrap facial hair, Moreno's Oscar is earnest and likable. Even Frog (paranoid with a mean streak) charms us through Wilkof's sensitive portrayal. With a change of clothes or a comb through the hair, costume designer Jessica Pabst helps chart the subtle transformations in these two men as they strive to succeed, in spite of significant hurdles. And then there's Emma, who seems to stumble over her hurdles on purpose in order to get attention.

Perhaps Schreck's story is too neat of a morality tale, with obvious heroes and villains. Still, that doesn't prevent the play from deeply resonating or feeling authentic. Under the direction of Kip Fagan, the events unfold in a surprising manner, even if we can guess the end destination.

Schreck cruelly holds out the possibility for a better world of redemption. This is not Les Miz, however, and Emma is most certainly not Jean Valjean. The more charitable and gullible audience members will howl that this girl is suffering from depression and needs our compassion. Yet that's an easy assessment to make from a safe distance. I doubt even Mother Teresa would have much patience for this supremely loathsome character.