When a Broadway Star Finds His True Calling…as a Financial Adviser

(© Joan Marcus)

In the decade between his 20th and 30th birthday, Ben Wright, Into the Woods's Jack, left the theater business no fewer than three times. On his third try, he finally succeeded (mostly). Though Wright does occasionally return to the stage for events like BAM's recent Into the Woods reunion, he's built his full-time career as a successful financial adviser and president of his own firm.

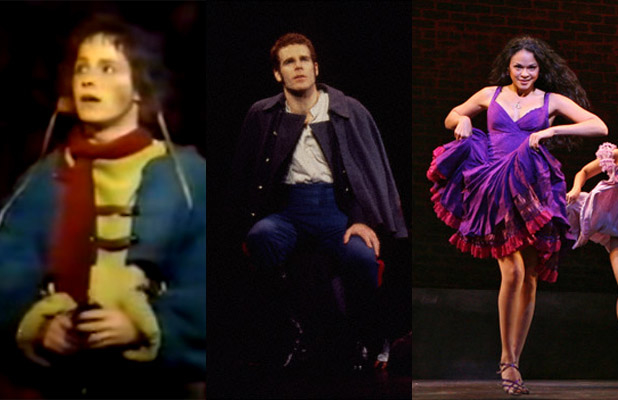

Though Wright found Broadway success, he came to the realization that he'd be more fulfilled by a life out of the footlight. His experience has been mirrored by other actors like Passion Tony nominee Jere Shea (who went on to become a Deputy Chief of Staff for Massachusetts Governor Paul Cellucci) and West Side Story Tony winner Karen Olivo (who teaches musical theater performance at the University of Wisconsin). These three lauded Broadway actors have very different stories, but what they have in common is that each was motivated by a deep conviction that they were being called — away from the Broadway stage.

"A lot of people just don't understand," said Wright, referring to his choice to step away from career that seemed hell-bent on making him a star. But, he continued, "it's one of those things where you have to listen to yourself."

Of course, in practice, the decision wasn't quite that simple. Wright's first attempt at leaving the industry came in his 20s after "living the life" in L.A. wasn't making him happy. Wright decided to go back to college because, in his "heart of hearts," that's what he wanted to do – a conviction that remained firm even when he was offered the chance to play John Hinckley Jr. in the original off-Broadway production of Assassins. While in school, Wright met and fell in love with actress Amy Gage. After they married, the two decided to try life on the East Coast, where Wright again found success, with roles in the film Renaissance Man and Hot Mikado at the Ford Theater. But again, Wright felt compelled to do something else with his life, and he soon left to work at his father-in-law's North Carolina-based company.

For almost anyone else, a move that definitive would have put the final nail in the coffin of a showbiz career. But Wright soon got a call inviting him to play the role of Wayne Frank in the national tour of State Fair. He would, he said, but only if the show would cast his wife as well. So Ben and Amy Wright toured the country together and eventually found themselves on Broadway. The run of State Fair was short-lived, and soon Wright found himself having to decide, once again, whether to actively pursue a theatrical career. Unsurprisingly, he chose to head back to North Carolina. This time it was for good, though Broadway did make one last ditch effort, offering him a role in Broadway's The Scarlet Pimpernel, which he turned down.

"I didn't feel like I wanted to be an actor," said Wright. "Sometimes things happen to the wrong people. My life just didn't feel authentic to me. I didn't feel like I was doing what I was put on the earth to do."

It's a refrain that's common — and accepted — among artists, but not as often heard among those who choose a less glamorized career path. When a primary care physician quits his job to become a full-time actor-comedian, for instance, no one assumes it's because he couldn't hack it as a doctor, while the converse can't be said about performers who choose to try a different career. Often, artistic talent and artistic success are considered to be the same as artistic calling. But the life choices of Karen Olivo and Jere Shea are two more reasons to believe that's not the case.

Though neither Shea nor Olivo felt a pull away from performing in quite the way Wright described, both of them did feel another call that was stronger than the bright lights of Broadway. For Shea, that other pull was family: "The one thing that I always wanted to be was a family man," he recalled. "I wanted to be married, wanted to have children." So when an acting career began to get in the way of that calling, Shea cut his losses and went looking for a more consistent job that would utilize his skillset and found the world of public relations and fund raising.

Likewise, Karen Olivo had no intention of turning her back on performing altogether when she announced via her blog in early 2013 that she'd be "starting over" in Wisconsin, and that she would "leave behind the actor" and "start learning how to be me." What she does seem to have been saying is that personal fulfillment, for her, did not lie in performing on Broadway. Olivo also elaborated on the way her success as an actor (including a 2009 Tony Award) has made it even more difficult for people to accept her choices. The idea of what people think you should be starts to factor into things even more, she said; "it gives you just a little bit more of 'now I have to prove something to people.'" Of surviving in the industry as a whole, she said, "It's a balancing act." There are "innumerable choices" as to how as to how a person lives out their artistry, and each artist's life can really take on any shape.

As Shea found the right balance and his life began to take its particular shape, he found that the two great motivators in his life, family and story-telling, would best be served at different times. Since his twins are now grown and left the family's Boston home, he's recognized a renewed desire to "be an actor and tell stories that move people and teach people." In fact, now that his focus is off his family, Shea has recently taken steps to reenter the theater profession and will soon be returning to New York.

In Wright's case, he had to figure out what career he was meant to pursue. He knew he wasn't comfortable as an actor, and yet, he recalls, "I didn't know what I was put on the earth to do." Eventually, he turned to financial advising, pursing a lifelong interest in investing money. In just 15 years he's set up his own independent advisory practice, but his life's real aha moment coincided with the birth of his and Amy's fourth child, their second with Down syndrome.

"When she was born and Amy and I realized how rare it was to have two biological children with Down syndrome, we sort of felt like, 'Oh, now we get it, this is what we're both supposed to do. We're supposed to go to bat and advocate for the value and acceptance and inclusion of people with Down syndrome,'" he said. Not only does Wright now sit on the board of directors of the National Down Syndrome Society, but also his financial advisory practice employs eight client hospitality associates, each with an intellectual or developmental disability.

After turning down the role he was offered in Assassins, Wright recalls running into Sondheim in New York: "He said, 'I guess it wasn't a big enough part for you, huh?'" Wright remembers replying, "Oh, please don't misunderstand," but perhaps the most apt response would have been one of Sondheim's own lyrics. In Into the Woods he writes:

Just remembering you've had an "and,"

When you're back to "or,"

Makes the "or" mean more

Than it did before.

Now I understand —

And it's time to leave the woods.