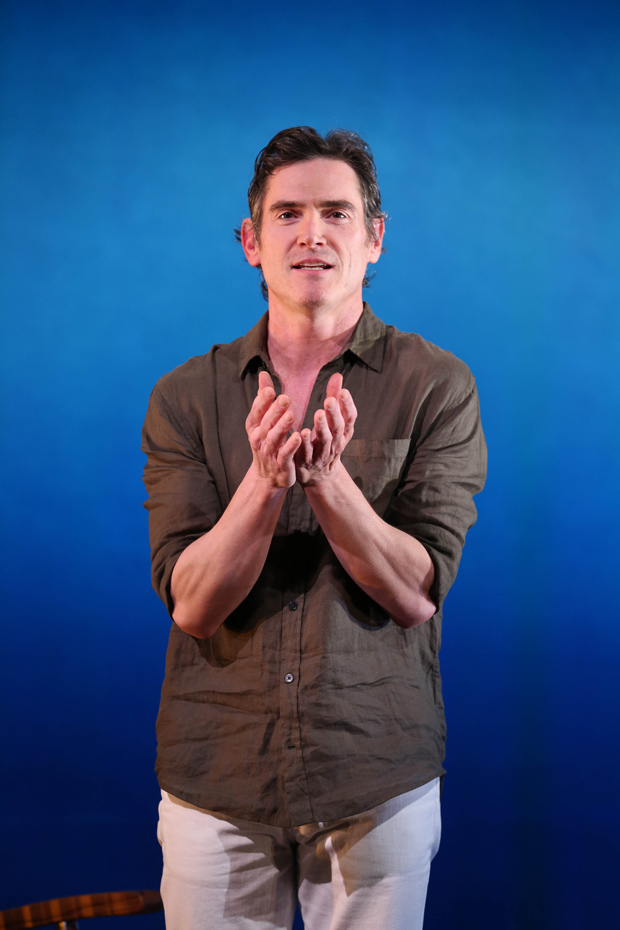

Harry Clarke

(© Carol Rosegg)

Philip Brugglestein may have been born into an average American family, but he's sure that there's an Englishman trapped inside of him. That's why he starts speaking in a poncy British accent at the age of 10, eschewing the aggressive vowels bequeathed to him by his manly Midwestern father. If that plotline reminds you of the film Breaking Away, in which an Indiana cyclist adopts an Italian accent, you are not alone. David Cale's Harry Clarke (now making its world premiere with Billy Crudup at the Vineyard Theatre) feels a lot like a story we've heard before. Somewhat derivative, this solo play is nevertheless an undeniably entertaining meditation on identity and deception.

That theme is emphasized by the fact that we are never quite sure who our narrator is: At first, it's Philip, the South Bend transplant who lives a solitary British life in New York City (he's never actually been to the U.K.). One day he decides to follow a man around midtown, just to see where he's going. They eventually land at a Dean & DeLuca, where Philip overhears the man having a very angry phone conversation with a woman named Sabine. Surprised to see that very same man seated across from him at the theater a few months later, he leans over and says hello in a thick Cockney accent very different from his usual modest received pronunciation. Philip also says that his name is Harry Clarke and that he's sure they've met before…through Sabine.

(© Carol Rosegg)

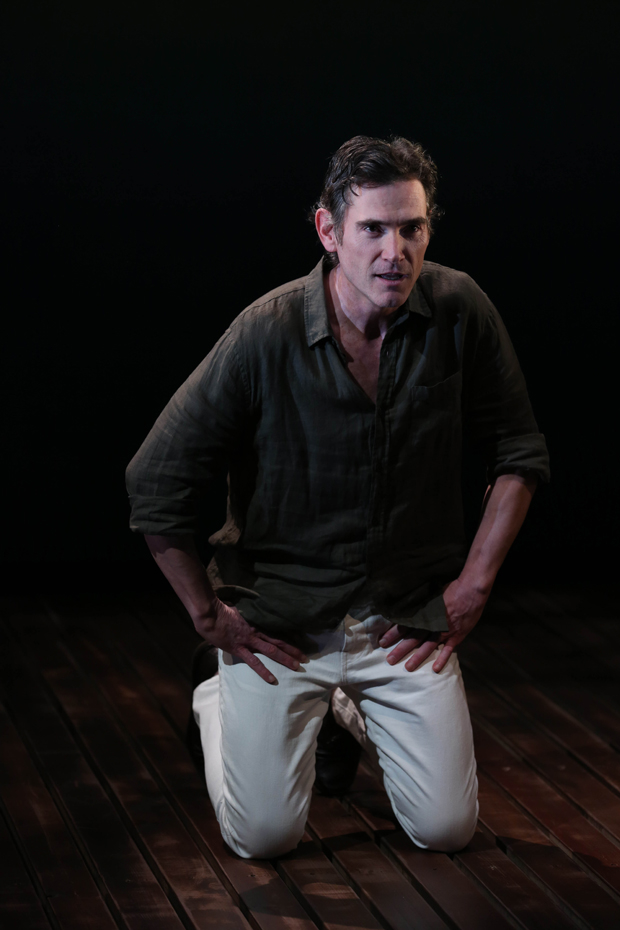

Taken aback, the man pretends to remember and says his name is Mark Schmidt. Instantly attracted to Harry's lusty confidence, he goes to dinner with him after the show. A week later, Mark invites Harry aboard his family's yacht. The two become intimate friends, with Mark confiding his darkest secrets in Harry. The self-involved Mark never suspects that Harry (or Philip) has secrets of his own.

The plot further contorts from there, but to say more would give away the pleasure of watching it unfold. This kind of solo page-turner narrated by an unbalanced protagonist has become very popular in the theater (Aaron Mark has written three in the past four year). This particular story of a charming bisexual who infiltrates a rich and credulous family has echoes of "The Talented Mr. Ripley".

Crudup is particularly convincing in both sexual and dialectical malleability, deftly juggling multiple accents (he also does the voices of all the American characters). Philip never sincerely expresses sexual desire of his own, but he knows how to arouse it in others through the strategic use of an alluring smile and unflappable self-possession. His relationship to Harry Clarke is that of an addict: He knows it's wrong to pose as this fictitious person, but the power it gives him is intoxicating. Without us fully noticing, Harry Clarke begins to take over the narration, consuming Philip like Mr. Hyde. We hang onto his every word, acutely aware that it could all be BS. He's spent so much time lying to everyone else; why would we be any different?

Director Leigh Silverman's unobtrusive staging puts its faith in Crudup and Cale's writing to hold the audience rapt, which turns out to be the right bet. The useful lighting (by Alan C. Edwards) shifts to denote the change of time and place, but Crudup rarely moves away from his central position near a deck chair on a patio. Unfortunately, this set by Alexander Dodge somewhat spoils the play's conclusion, as does Kaye Voyce's casual beach costume. We know Philip-Harry isn't telling us this story from a prison or mental institution.

(© Carol Rosegg)

The discomfort we feel in Harry Clarke may derive from the knowledge that, to a lesser extent, we all indulge in this kind of fronting. We play roles in our professional and personal lives in order to get what we want from both. Cale's play begs us to consider the question: In the dark solitude of the night, who are you really?