Blueprint Specials: U.S. Vets Join Broadway Stars in Lost Frank Loesser Musicals

(© Ashley Garrett)

Straight out of graduation from her Oregon high school, Sandra W. Lee was accepted to the Tisch School of the Arts musical theater program. She opted to stay put in Portland and study opera, but before Lee could finish her schooling, her life was upended by the tragedy of September 11, 2001. In the fallout from that day, she decided that she wanted to be a part of something greater than herself and soon enlisted with the U.S. Army.

"I wanted to be able to look back on my life and know that I did everything that I could make the world a better place," she recalls, "to have some kind of positive impact for my friends, my family, my community."

(photo provided by O&M Co.)

By the mid-2000s, Lee was fulfilling those goals, rebuilding war-damaged schools in Iraq. But that deployment would prove to have a more damaging impact on Lee's own life than she could have imagined: "I subsequently became a disabled veteran due to traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress, as well as military sexual trauma," she explains.

Lee left the Army in 2010, finishing out as a Staff Sergeant, but her struggles with the military community didn't end there. Because of issues with the Veterans Affairs system, Lee ended up becoming homeless after six months at a post-traumatic stress hospital. Now, with the help of organizations like Purple Heart Homes and the Veteran Artists Program, Lee is living what she calls "a somewhat normal life" again.

At present, she's appearing in Waterwell's Blueprint Specials, a production notable not only because it marks the first staging of four long-buried Frank Loesser musicals in more than 50 years or because it brings the Public's Under the Radar Festival to a retired aircraft carrier. The most special aspect of the upcoming production is that it aims to bridge the gap between America's military service people and civilians by employing members of both groups in one off-Broadway show. The production stars Tony nominees Laura Osnes and Will Swenson.

(photo provided by O&M Co.)

Lee's participation in the production raises a question: Why would a veteran with so many negative experiences choose to actively associate herself with her military background?

Her answer is that this is all part of a long healing process, of not having to emotionally separate the piece of herself that she describes as "proud to be in the military and proud of what I have done."

"I had pushed that all away and now it's coming back around," she continues, "and it's led me to this point, to be in this particular show." In fact, the experience is bringing back a lot of the positive memories she has of her time in the Army. "The sense of camaraderie that we're developing is very much like the military community," she says. "So it's been really good."

According to Lee, the gulf between the military experience and the theatrical experience is not as wide as one might expect. The worlds of the military and the performance arts are both built on "camaraderie and community" and see themselves as working toward "a greater good."

(© Ashley Garrett)

Blueprint Specials director and Waterwell co-artistic director Tom Ridgely believes that in an admittedly small way, his show is more than succeeding at the self-assigned task of bridging the ever-widening gap between those who have served in the armed forces and those who have not. His cast, he says, is edging toward a cohesive community unseen since the days in which the blueprints were first written.

"Most Americans don't have a personal connection to the military the way they did in, say, the 1940s," he suggests. Broadway star and cast member Will Swenson adds, "We as a nation have created a bit of a divide. After Vietnam we stopped the draft, so service was selective and not mandatory."

(© Ashley Garrett)

But within the microcosm of Blueprint Specials, he says that conversations between the two groups are opening eyes. From Lee's perspective, it feels as though her civilian castmates are learning that there isn't really a divide between service members and civilians: "I think that opportunities like this, [they] show that the military is made up of people like you and me and everyone else. You know, we're not just veterans. We all go through the same life experiences and the same emotions and the same heartache and joy."

"We're creating one community with this show," she adds, "which I think is just fantastic."

With Blueprint Specials, Waterwell aims to take the bridge-building one step further, inviting audiences to experience the improbable community they've created. "If we're doing our jobs right, we can provoke introspection and ask questions that maybe you wouldn't normally ask yourself if you weren't witness to the piece of art," says Swenson. "Hopefully [it] opens your eyes."

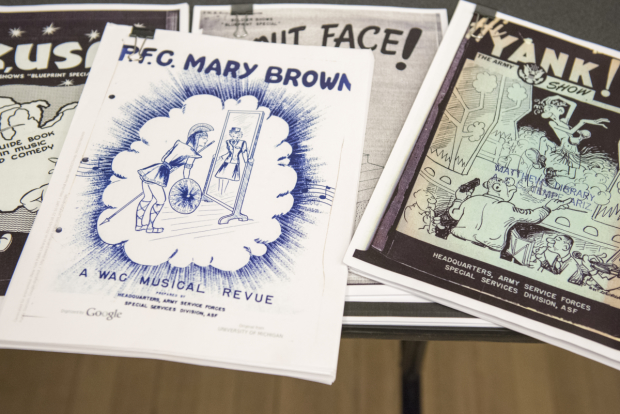

Blueprint Specials is uniquely positioned to do just that. When first created by future Guys and Dolls Tony winner Frank Loesser, they existed for the express purpose of building camaraderie among World War II GIs. According to Ridgely, the military-commissioned musicals were packaged as a giant book that could be taken anywhere in the world. It included not just the script, but also complete orchestrations as well as scenic and costume designs and instructions (hence the "blueprint" label). "They say things like take a GI trash can lid and do this to it, and voilà! You have a shield," laughs Ridgely. "Take a medic's jacket and cut off the sleeves and attach crepe paper and now you're this character."

According to Swenson, the whole thing feels like a big inside joke. "If you were in the military in the '40s," he says, "it would feel like the company party where you're making fun of, 'Oh, Kevin's the guy that always eats all the food' — that kind of stuff."

In that sense, the pieces, which Swenson calls "squeaky clean," were subversive because they were able to poke fun at military culture. Ridgely believes that decision was a conscious one. He thinks the army realized the soldiers needed "a release valve," "a way to react to the specific environment of the military in a way that was safe but also sort of transgressive at the same time," and of course, to come together in satirizing their situation.

Waterwell is also going one step further toward bringing Blueprint Specials audiences into their newly created world by staging the show on the Intrepid, an aircraft carrier built around the same time Loesser was writing the blueprints.

(© U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation)

Ridgely believes this creates an immersive environment that simply can't exist anywhere else because of the sheer scope of the ship: "I mean you're walking, like, city blocks [within] this giant military object where the shows are happening."

Lee agrees. "It's in an element that will bring the audience more into the show," she says. "They'll actually feel like they're an active participant rather than a spectator." Her hope is that the immersive experience will fulfill their goal of "[bringing] others into [our] realm for a couple of hours — so that they can sense that feeling of community that we've shared and developed."

Today's veterans often feel an imposed sense of otherness upon returning to the civilian world, Ridgely believes, and because of that, it can be incredibly hard for them to accomplish the difficult transition of leaving behind the military culture and reintegrating with their community: "We [want to] help with that. [We hope] we can start to try to address it in a way that hasn't been addressed already."