Rasheeda Speaking

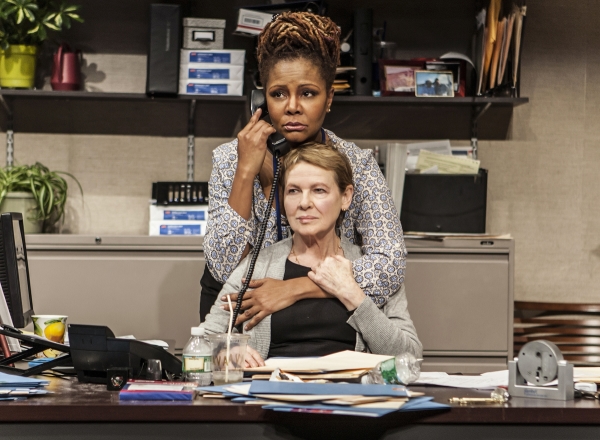

(© Monique Carboni)

"I don't see race," goes a popular lie. In reality, race and racism are ubiquitous features of the American landscape, as unavoidable as interstate highways and fast-food restaurants. It's likely to remain that way long after we are all dead, no matter the skin pigmentation of our president. Joel Drake Johnson takes on the myth of "post-racial" America in Rasheeda Speaking, now making its New York debut with the New Group at the Pershing Square Signature Center. Equal parts funny, frustrating, and fascinating, it's a clear-eyed look at our shifting language and attitudes around this perpetually sensitive subject.

The play takes place in the beige office of Dr. Williams (Darren Goldstein, looking and sounding every bit like an aging-bro-cum-surgeon). Set designer Allen Moyer stuffs the space with paperwork, files exploding off the shelves. Potted plants dot the room, bringing a smidgen of color to the typically drab office space.

In a Machiavellian gambit, Dr. Williams has promoted Ileen (Dianne Wiest) to office manager, even though there are only two receptionists. As part of her new job, Ileen is to keep an eye on Jaclyn (Tonya Pinkins), the other (black) receptionist. The doctor doesn't like Jaclyn's attitude and wants her out, but he needs to make a case with HR. "It's hard to get rid of people today — with all the tricks that Human Resources can pull out of their hat and those superficial laws about harassment," he complains, using barely coded language.

"The race card, you mean," Ileen correctly identifies the doctor's dog whistles, leading him to blanch like she just said "Voldemort" out loud. As she has so often in her career, Wiest plays the jovial and habitually well-intentioned naïf. It's impossible not to like her, or feel bad about the position the doctor has put her in. You get the sense that she genuinely wants everyone to get along and that she hasn't really spent much time considering why that is impossible.

Jaclyn, on the other hand, is far less predictable. Pinkins plays her cards close to her chest, adding to our ambivalence. We laugh at her antics and prodigious wit. We're also thankful she's not our coworker.

The arrival of dotty septuagenarian patient Rose Saunders (Patricia Conolly) gives us some sense of the doctor's grievance with Jaclyn: She's brusque with the patient, chiding her for not checking in on the first floor. She hands her forms that she's already filled out. "Each time you return, you have to do it again," she says, brushing off Rose's protest. Ileen observes with a clenched jaw. Doesn't Jaclyn understand that the byzantine rules of America's unnecessarily complex medical bureaucracy don't apply to sweet old white ladies?

Conolly deftly captures the cheerfully oblivious racism of the elderly. When Jaclyn apologizes for their earlier run-in, Rose offers, "My son thinks it's in your culture to act the way you did…something about your way to get revenge for slavery." One might easily dismiss this as a bygone opinion if it weren't so clear that the doctor harbors similar thoughts. Even Jaclyn expresses her own, far less veiled bigotry: "Deport them, God, please deport these people out of my life," she clucks about her Mexican neighbors. In Johnson's world, everyone's a little bit racist.

Pinkins gives one of the most beguilingly layered performances of the season. She's intense, practically prosecutorial in her interactions with Wiest, taking passive-aggressive to a whole new level. Jaclyn subtly bullies Ileen while maintaining plausible deniability. One moment she's secretly moving things around on Ileen's desk; the next she offers Ileen a giant potted plant and a hug. By the end, both women are completely consumed with paranoia, scanning each other for hidden strategies like chess masters in a high-stakes tournament.

In her directorial debut, Cynthia Nixon expertly stages these frenemy skirmishes. A nameless terror is palpable throughout. Pandora-like, Jaclyn offers Ileen a wrapped gift as a peace offering. Coffee quietly percolates in the kitchenette, giving voice to the unspoken tension between the two women. Costume designer Toni-Leslie James outfits Jaclyn in aggressively African prints and a tall column of tightly braided hair. Her look becomes increasingly conservative as the play progresses and Jaclyn makes it clear she's not going anywhere.

The play focuses a magnifying glass on how much energy we expend furtively pursuing these racially charged mind games. One gets the sense that we could be so much more productive if we could dispense with such petty tribalism and move forward as Americans, united as one people. After seeing Rasheeda Speaking, you won't hold your breath for that day to happen anytime soon.