The Good and the True

(© Jeremy Daniel)

Sometimes, the best way to serve a story is to get out of its way. Creators Tomas Hrbek, Lucie Kolouchova, and Daniel Hrbek have held this philosophy at the core of The Good and the True, which weaves the firsthand accounts of two unrelated Holocaust survivors into a single staged piece. Translated by Brian Daniels for its American premiere at DR2 Theatre, the creative team handles the pair of testimonials with delicacy, abstaining from manipulative embellishments in favor of raw depositions, allowing the simple yet haunting stories to radiate with unadulterated authenticity.

The Good and the True takes its name from its two historical centerpieces — Czech athlete Milos Dobry and Czech actress Hana Marie Pravda — both of whom were imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps during World War II. Dobry, whose surname in Czech means "good," was born with the name "Gut" (the German word for "good"), which he translated after the war in order to separate himself from all things German. Pravda's name, meanwhile, translates in her native Czech to "true."

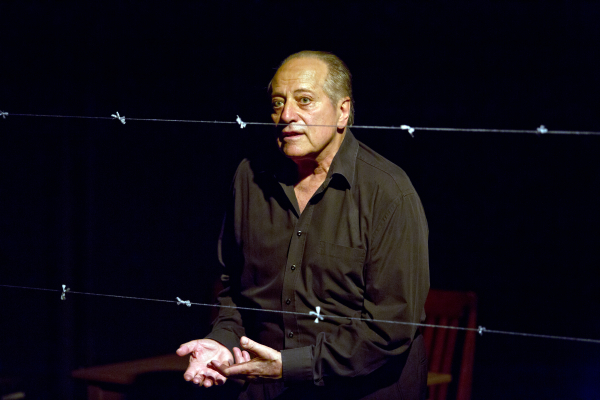

The principle behind the piece is as profoundly simple as its title. On a stage split down the center by a train track covered in stray shoes, Dobry and Pravda take turns delivering excerpts from their stories to the audience through a barbed-wire fence (a striking design by director and cocreator Daniel Hrbek). Karel Simek's lighting design shifts our focus back and forth between their tales, while also adding dramatic accents to the details of their stories — though not much accenting is needed for their impact to land with full force — just a pair of capable storytellers.

The production finds this and then some in Saul Reichlin and Hannah D. Scott, who relate their characters' heartbreaking reminiscences with captivating intensity, built on a foundation of understated charm. Reichlin, who originated his role in the piece's U.K. and Belgian touring productions, offers a performance filled with the juices of this long-term marination. He tells of Dobry's journey from Prague as a young Jewish student to the concentration camps of Terezin and eventually Auschwitz with a youthful enthusiasm and naïveté that drains from his face as both he and the story march on.

Scott matches Reichlin's high bar, delivering an impressively nuanced performance without the same benefit that time has afforded her costar. Due to international red tape and a work-visa catastrophe, the part of Hana Pravda, which was originally to be played by Pravda's real-life granddaughter Isobel Pravda, was handed to Scott just days ago. She has taken up this fresh material and shaped Pravda into a character whose transition from childhood as an aspiring young actress into adulthood as a seasoned performer, hardened by her torturous experiences, takes on a robust, three-dimensional life. She speaks with a soft sweetness that nevertheless conveys a substantial depth of wisdom, though a wisdom achieved through the most unfortunate of circumstances. While the production's logistical challenges were unanticipated and certainly unwelcome, they are almost poetically fitting for this triumphant piece. In the face of adversity, goodness and truth have once again prevailed.