The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner

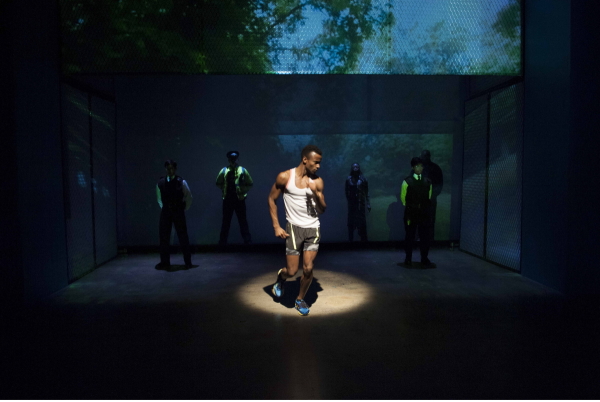

(© Ahron R. Foster)

As the pain-faced foil-wrapped New York marathoners can attest, the serenity of a long run is unparalleled by any other solo activity. Escaping the headache of daily stressors; letting your thoughts wander wherever they so choose; being plugged into nothing but your mind and body for a pocket of uninterrupted time — these are all privately transcendent experiences that can feel cheapened when put into words. This is the unfortunate paradox in which Atlantic Theater Company's new stage adaptation of The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner finds itself.

British playwright Roy Williams has translated the politically charged tale for the stage, offering a modern-day interpretation of Alan Sillitoe's original 1959 short story, which Sillitoe then adapted for film in 1962. The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner attempts to dissect the mind of Colin Smith (Sheldon Best), a troubled hoodlum from a working-class family in the UK. As he struggles internally with the death of his father (Malik Yoba), his mother's new beau (also Yoba), and a distaste for authority, an act of petty theft with his friend Jase (Joshua E. Nelson) lands him in prison school alongside unwelcoming classmates Asher and Luke (Eshan Bay and Patrick Murney). However, the clever little bugger finds a loophole. Noticing his natural talent for long-distance running, the school hopes to make an example of Colin, pitting him against the upper echelon of society in a government-sponsored student race. To prepare for the event, Colin is afforded an hour of freedom each day to train out in the open air, all by his lonesome.

Best's impressive musculature, accentuated by the mesh tank he dons (selected by costume designer Bobby Frederick Tilley II) for the duration of the 80-minute play makes for a striking first impression of our protagonist. If only his psyche were as hard to crack as his biceps, this brooding character would be far more compelling. The play is structured as a series of flashbacks stemming from Colin's wandering mind during the pivotal race. As he transitions between these remembered dialogue scenes and the outwardly spoken internal monologues he recites center stage while jogging (impressively, without getting winded), there is little discernable shift in tone. For a withholding young man whose private thoughts are his greatest treasure, Best and director Leah C. Gardiner have settled on a very affected interpretation of the character. The thought she shares during the race should feel like an outpouring of suppressed emotion, like steam escaping from a pressure cooker. Yet Best's consistently energized manner of speech and movement pokes a few premature holes in the pot, diminishing the explosive power that these private insights could have offered.

Placing the dramatic thrust of a play on spoken thought is a tall order on which Williams' script does not completely deliver. The most poignant internal meditations are the most difficult to put into words, like accurately translating a classic text into a foreign language. Williams only dips a toe into this deep emotional well, offering little beyond a repetitive description of Colin's love of running. He does, however, intelligently repurpose the original story — which was embedded in post-World War II British climate of class differences and criminal activity — to fit the country's contemporary political environment. Videos of Prime Minister David Cameron (designed by Paul Piekarz), a man frequently accused of social elitism, are projected around the stage. His image becomes a specific target for Colin's anger and distrust of authority, most of which he directs toward his school overseer Stevens (Todd Weeks) whose motivations to make Colin participate in the race are questioned until the very end. However, as Colin and Stevens plod through this clunky game of cat-and-mouse, you feel like slapping a piece of duct tape over the mouth of the rebellious young man and saying "just go run it off."