The Crucible's Historical Melting Pot

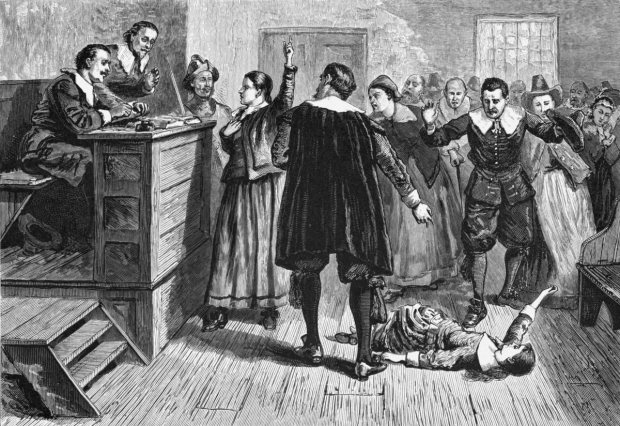

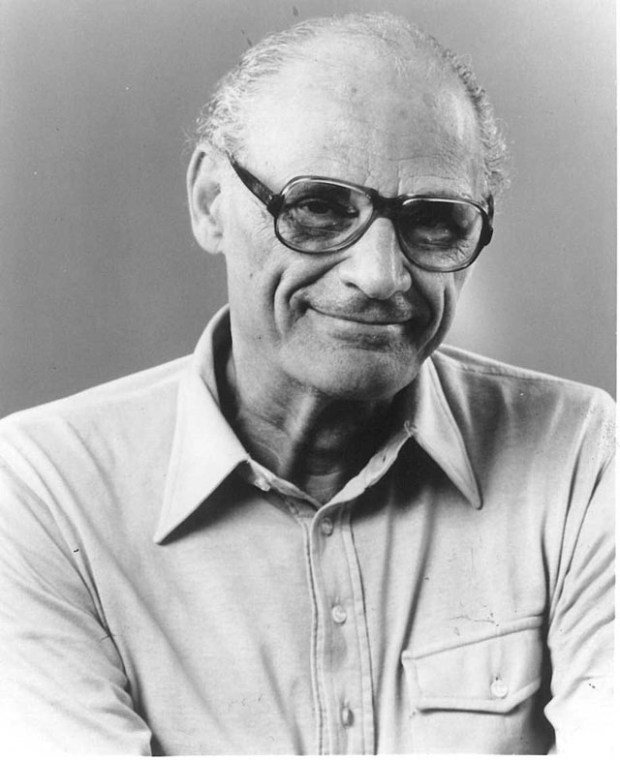

"God's icy wind" does indeed blow onstage at one point in Ivo van Hove's new production of The Crucible, as predicted in the well-known speech that closes the play's Act 2. A wolf briefly roams the stage (actually it's a well-trained Tamaskan, a new breed with a lupine look), as wolves roamed Salem's roads in 1692. A girl levitates, as "bewitched" girls ostensibly did in Salem (and as Rwandan girls apparently did in the events dramatized last year in Katori Hall's Our Lady of Kibeho). Whatever one thinks of van Hove's direction (of which this is not a review), it evokes, undeniably, the source material in which Arthur Miller's familiar play is steeped. That grounding inevitably makes me think about the parallels between the Salem village witchcraft trials and the anti-Communist witch hunts of Miller's own time, both ancient events that still resonate today.

Miller's analogy has often been challenged, on the debatable ground that there were no witches in Salem, whereas there were Communists in the post-World War II U.S. Neither assertion is wholly exact. Most probably, Salem village in 1692 held no practicing witches — not, at least, as the ministers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony defined witches: persons who had signed over their souls to Satan, getting in return certain supernatural powers here on earth. The deal was a proverbially bad one, and New Englanders to this day are proverbially cautious deal-makers. So Salem's outbreak of collective hysteria, in which 20 people, including 14 women, were executed for witchcraft, had no basis in fact. Having begun with overexcited prepubescent girls, it was probably in large part a product of group fantasy.

But perhaps not entirely. Religion was a central fact of colonial life, and New Englanders watched one another, hawklike, for imperfections of faith. Factionalism ran high: The Bay Colony's Puritans, as Stacy Schiff points out in her recent study, Witches: Salem 1692, were apostates twice over — from Rome and from the Church of England. And the colonists had brought superstition, like religion, with them from England. The colony's ministers, learned but not particularly enlightened men, had little understanding of it. To them, the phrase "pre-Christian survival" would have meant only a pagan sinfulness to be shunned as devils' work. If you unthinkingly knocked wood for good luck, or tossed a pinch of salt over your left shoulder while cooking, and someone saw you do it, you might get denounced in church.

More arcane folk traditions survived too. Medical science had barely been born then — its early remedies sound to us more like witches' brews — and doctors were few. People treated ailments or injuries with the same methods, mostly herbal, as their ancestors. Every household kept its stock of "simples" known for their various curative powers. Midwives, trained in the properties of old-world plants, were busily exploring, or learning from Native Americans, the uses of those growing here. From chamomile and eyebright, it was only a short step to potions that would keep your husband from straying, or make the neighbors' son notice you. Harmless nonsense to us, but a Massachusetts clergyman of 1692 might well have called it Satanic.

More such superstitions arrived with indentured servants, who might have come from anywhere, or with slaves: Reverend Samuel Parris, in whose parsonage the manifestations began, had been a planter in Barbados. Nobody knows the origin of the slaves he brought with him to Salem, Tituba and a man known only as "John Indian" (surely the first "invisible" nonwhite male in American history). Scholars have found sources for Tituba's name in European languages, Yoruba, and Arawak; her heritage may have been as much a mixture as her jumbled, flamboyant confession.

The Salem witch trials cast their shadow over American culture long before Miller: Hawthorne (whose ancestor was one of the presiding judges), Longfellow, and barely remembered novelists like John W. DeForest and Esther Forbes all preceded him; Mary Wilkins Freeman essayed a play on the subject, Giles Corey, Yeoman, in 1893, 60 years before Miller seized on Corey as a key figure. Salem had found its way to Hollywood, too: Fred MacMurray rescued Claudette Colbert from being executed for witchcraft in Paramount's Maid of Salem (1937), which featured the black actress always grandly billed as "Madame Sul-Te-Wan" (real name Nellie Crawford), as Tituba. A few years after The Crucible's premiere, Shirley Jackson — celebrated for her spooky contemporary novels and short stories, like "The Lottery" — turned Salem's turmoil into a children's book, The Witchcraft of Salem Village (1956). So remote and yet so dramatically immediate, the story remains a touchstone.

Reading about the trials now, it is easy to see why their raucous, fevered atmosphere evoked for Miller the divisive turmoil that surrounded him in the era of Senator Joseph McCarthy and the HUAC hearings. The worldwide depression of the 1930s had led many to find hope for a better economic system in various brands of socialism — Communism, as promulgated by Soviet Russia after 1917, first among them. Many American leftists had problems with both the USSR and our homegrown Communist Party (CPUSA). The latter's power struggles and factional splits, which mirrored those of Russia's ruling elites, were exacerbated by the USSR's insistence on setting Party policies worldwide. CPUSA membership fluctuated, declining with pivotal events like the Moscow purge trials, the expulsion and assassination of Leon Trotsky, and the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939. Even so, large numbers of Americans who had seen capitalism's brutal effects — millions unemployed and starving; armed militias firing on striking workers — retained sympathy for both the CPUSA and its economic ideals. When the USSR became an ally against Hitler in 1941, many put aside earlier misgivings for the duration of the war.

But were such people, strictly speaking, Communists, any more than those accused in Salem were witches? I'll ponder that and other relevant questions next week.