How Broadway's Curious Incident Is Putting One of Literature's Most Fascinating Minds Onstage

When it comes to theatrical adaptations, set designers rarely have to deal with the same audience pressures that writers and directors are accustomed to. But in the curious case of recent West End hit The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, designer Bunny Christie felt the full brunt of fan expectations.

"Everybody in the U.K. knows the book. It was just a phenomenon in the U.K.," says Christie. "So when I was designing the show, anybody [who] said to me, 'What are you working on now?' and I said Curious Incident, they went, 'Oh I love that book. I love that book.' People would regularly say, 'That's my favorite book of all time.' I was like, 'Could you stop saying that? It's so much pressure.'"

Christie clearly works well under pressure. Curious Incident won a 2013 Olivier award for her design and the production has now transferred to Broadway. TheaterMania spoke to Christie about how she used artistic collaboration to get inside the head of a one-of-a-kind 15-year-old.

(© Joan Marcus)

How did you begin the process of designing such an unconventional show?

We did some workshops very early on at the National Theatre studios and that was with a bunch of actors and the script. We were trying out ideas of how we would make somebody fly through space and investigate into different rooms of a house if we didn't have lots of set-changing. And that was really useful for me because I was just watching actors play and be very imaginative and almost create things the way that children play games.

(© Joan Marcus)

The actors' movements feel like a part of the set. How did you integrate those elements?

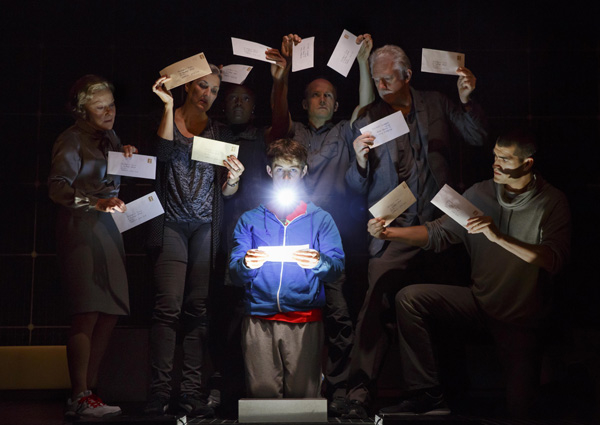

Because we were all working together very early on, I saw how much the company could create with very little. Then we could support that with sound and light and atmosphere. We could be really kind of playful around them. I was also very keen that it felt like we were kind of inside his head and that the set feels like it's his brain. And that the other actors around Christopher sometimes are almost kind of microbes inside his body.

(© Joan Marcus)

A set that seems realistic to the typical audience member probably wouldn't feel realistic to the character of Christopher.

[Director] Marianne [Elliott] and I started with the script and quite quickly I sort of felt like it needed to be a world that Christopher felt comfortable in and it felt like a world of technology and maths and science and all the elements that he likes. So sometimes the set can feel like he's very in charge of it and the technology is his friend, and then other times in the same way that the kind of chemicals in his head get out of balance and he's not in control of that, the same thing happens to the set.

There's loads of lovely, lovely stuff in the book. There's fantastic illustrations, little drawings and maps which we really tried to include in the design and also descriptions of what people wear. Christopher doesn't look at people's faces. He very often describes what people's shoes are or what color T-shirt they're wearing. And so we really tired to honor that. There are lots of things that people wear in the show that's a direct lift from how he describes them in the book.

(© Joan Marcus)

Did you always expect that Christopher would interact with the walls of the set?

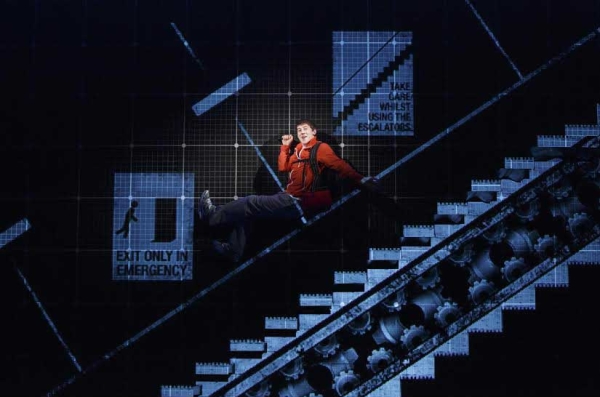

Actually, funny enough, when we very first did it at the National, we did it in the round. We didn't have any walls. Everything happened on the floor. So originally when we were moving into the West End, we were thinking, "Should we try to find somewhere where we could do it in the round?" and I was a bit like, "Well, I think it would be really exciting actually to have walls and to be able to use them." Sometimes it feels like the walls are the floor. So when he's walking he kind of walks on the walls but it feels like he's walking on the floor, and it's like the whole world is tipping and you don't know what's up and what's down. So for me it was really fun to then move into a theater where we had walls. And we had the moving back wall and we had the escalator. So he could walk down the wall. That was really good fun to chuck in the mix when we moved venue.

(© Joan Marcus)

Can you elaborate about creating the escalator effect?

The escalator thing is quite a big bit in the story and when I thought about it I thought, "We'll probably never get away with this." But hey, that's kind of what you do…But then I did sort of have a three-o'clock-in-the-morning moment of thinking, Oh my god is that actually going to be all right? You've got somebody coming down a staircase as the wall is moving down stage in real darkness with kind of flashing lights, and is that actually a crazy thing to be doing?

Originally we were gonna have each step come out individually and light up a bit like a kind of Michael Jackson staircase. Actually it works better when it all comes out together and it doesn't light up so you can't quite see how he's coming down the wall at first.

(© Brinkhoff/Mögenburg)

Where did you draw inspiration for all of the production’s many unique elements?

In the U.K. we have what are called A Levels. They're like your final exam when you're in school. And I went and got those exam papers. There are lots of lovely charts and Venn diagrams and x- and y-axis coordinates. It became obvious how useful that was because you can hide so many things in it. The nature of it means that you can't really see where there are doors or drawers or cupboards. And Paule Constable, who's the lighting designer, and I, we spoke a lot about wanting it to feel like it was kind of fizzing with electricity and really alive with light and energy so that that dark space could really crackle with electricity and energy and liveliness.

I think we really wanted to appeal to young people. It needed to feel like a cool space so when people came in, maybe people who don't generally go to the theater, it felt like a club or somewhere really exciting. I looked at quite a lot of computer games and wanted it to have that kind of feel so it didn't look like a stage set, really. We all said, for this production, let's really celebrate the geek. Do you have that expression in the U.S.? Let's really investigate all the things that Christopher would really like and have really good fun with that.