Bert Williams: America's First Black Star (Part II)

This is part II of Michael Feingold's latest "Thinking About Theater" column.

Click here to read part I.

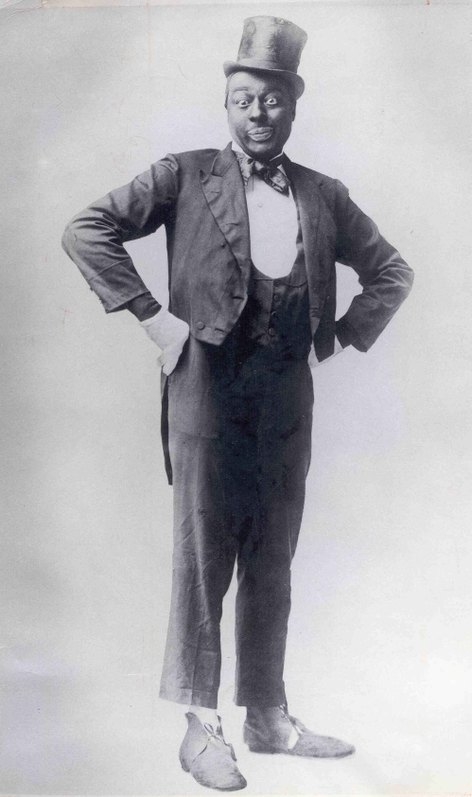

When Bert Williams and his partner, George Walker, began to create some of the first musicals written and performed entirely by African-Americans (though customarily with a white producer as enabler), the roles they performed onstage gradually evolved away from the era's familiar minstrel-show conventions toward a more universal brand of comedy. Walker — trim, wiry, and nattily dressed — was the suave sharpie whose schemes, virtually guaranteed to collapse, would invariably do so directly on the head of his sidekick, Williams' slow-moving, slow-thinking, chronically suspicious bumpkin, tricked out with character names like Shylock Homestead or Skunkton Bowser. The pairing was classic: History bulges with examples of it, from ancient Greek comedy down to the Hope & Crosby of the Road movies.

As the Archeophone recordings attest, the songs in these shows gave Williams some freedom from that character. In addition to bemoaning his own misfortunes ("There It Comes Again") or money troubles ("When It's All Goin' Out and Nothin' Comin' In"), he could narrate, and comment wryly on, events from ordinary life ("Let It Alone," "He's a Cousin of Mine"), or even, within the cartoon terms of early musicals, celebrate African heritage ("In My Castle on the River Nile").

Following Walker's tragically early death, Williams moved into solo stardom in vaudeville, and in the Ziegfeld Follies. There, he widened his reach, using his song numbers, mock sermons, and storytelling to move the incidents they narrated even further from the minstrel-show clichés in which they had begun. Marital squabbles, hardhearted employers, fights over gambling debts, maleficent doctors, preachers with dubious private lives — these were afflictions that could strike any ethnic group. Williams' selection and delivery of his materials made clear that he viewed them as universal. His vocalizings of what were ostensibly his own woes — his signature song, "Nobody," perpetually in demand, spawned many sequels — conveyed this empathetic feeling even more intensely, and they still convey it on record. It's hard to imagine anyone unable to identify with "My Last Dollar," or his Prohibition-era lament, "Everybody Wants the Key to My Cellar."

Williams' mellow, slightly grainy high baritone, with its rhythmically supple, vaudeville-style talk-sing delivery, was a matchless instrument for conveying a comic point. His difficulties, when working for Ziegfeld, came with his sketch material: His roles were limited to those in which a mainstream audience of the time could conceive a "colored" man — Pullman porters, apartment-house doormen, and the like. With the growing success and increasing lavishness of the Follies, he also found himself competing for space and material with an ever-expanding roster of extraordinary comic artists: Ed Wynn, Fanny Brice, W.C. Fields, Will Rogers, and Eddie Cantor. They revered him — Fields and Cantor in particular became close friends — but the crowding brought frustrations.

In one memorable sketch, he and Cantor, both in blackface, played a Pullman porter and his son just home from college — who, to the porter's embarrassment, turned out to be an overdressed, attitudinizing sissy. The homophobia underlying the joke suggests the extent to which blackface served functions beyond its demeaning intent: It could be used to broach topics, like homosexuality, that could not otherwise be publicly discussed. (It could even take on political implications: In the 1930 film version of Ziegfeld's 1928 stage hit Whoopee, you can see Cantor, in blackface, being forced by a bigoted sheriff to sing and dance at gunpoint.)

Given the endless barriers faced by all African-Americans in his time, it's easy to see why numerous anecdotes depict Williams becoming, over time, withdrawn and melancholy. (W.C. Fields famously called him "the funniest man I ever saw and the saddest man I ever knew.") Yet an equal number show him sternly resisting racism, determined to break down its barriers whenever possible. (Cantor tells of a bar in which Williams ordered a glass of gin. The bartender said, "That'll be $50." Williams pulled out a $500 bill and said, "I'll take ten.") His recordings reveal no waning of energy. The 1913 film discovered by MoMA shows a big, warmly gregarious man — in blackface (unlike the rest of the all-black cast) — but avoiding any hint of exaggerated or stereotyped behavior.

Ron Magliozzi, the MoMA curator who researched and assembled the footage, theorizes that the film went unreleased because the enormous success of D.W. Griffith's 1914 film The Birth of a Nation, which triggered a new rise in racism (including the rebirth of the KKK), made a feature film about the ordinary life of black people untenable in the market. It may be so. Certainly there was nothing in Birth of a Nation to make Williams, or any other person of color, very happy.

Yet his stardom, and his artistry, continued. When he died in 1922, at 47, he was in tryouts for a new play, The Pink Slip, in which he played a wily hotel bell captain who oversees the guests' romances — Williams' first step into "legit" comedy. And in our time, he has inheritors: Young African-American artists like Branden Jacobs-Jenkins and Robert O'Hara now dare to experiment with the stereotype imagery so long shunned.

One highlight of O'Hara's recent Bootycandy at Playwrights Horizons was a hilarious mock sermon that harks directly back to Williams' song "It Ain't Nobody's Business but My Own." And Williams, who thought it funny to have a character declare that "Iwilla" was a name from the Bible (as in the phrase "Iwilla, rise!"), might well have smiled at O'Hara's scene of a "non-commitment ceremony" between two black lesbians named Genitalia and Intifada. If history's caricatures are painful, Williams knew, the best way to survive is to build on the pain and laugh at it.

Michael Feingold's next two-part "Thinking About Theater" column will appear on consecutive Fridays November 21 and November 28.